Fishery This and That

Booming in the Edo Period

In the Edo period (1603-1867), the shogunate restricted fishing to the government's territory and imposed restrictions on the size of boats. Under these restrictions, basic fishing methods were established: seine nets were used on shallow sandy beaches where large nets could be easily drawn; line fishing was used on rocky or stony beaches unsuitable for seine nets; and fixed shore nets were used in fishing grounds where the topography and ocean currents resulted in large fish populations.

In Kujukuri-hama on the Boso Peninsula, sardine seine fishing started mainly among itinerant fishermen from Kishu (in present-day Wakayama and Mie prefectures). Since Kishu's mountainous terrain is close to the sea, there was originally little arable land. Furthermore, the farmlands were devasted by the long war, so the second and third sons of farmers found a way to make a living by fishing.

There are two types of seine nets: "double-handed", in which two boats work together to surround a school of fish, and "single-handed", in which one end of the towline is fixed to the shore and the net is laid by a single boat. At Kujukuri-hama, double-handed method was used, and about 200 people would haul the nets onto the beach, where most of the sardines were transported by boat to Osaka as hoshika (dried sardines) to serve as fish fertilizer for cotton farming.

Since ancient times, the Ainu people of Hokkaido have used nets to catch herring. Meanwhile, the Matsumae clan introduced "gill net fishing", in which nets are spread along routes taken by the fish, catching the fish by entangling them in the net. Gill net fishing was the method of choice during the spring spawning season.

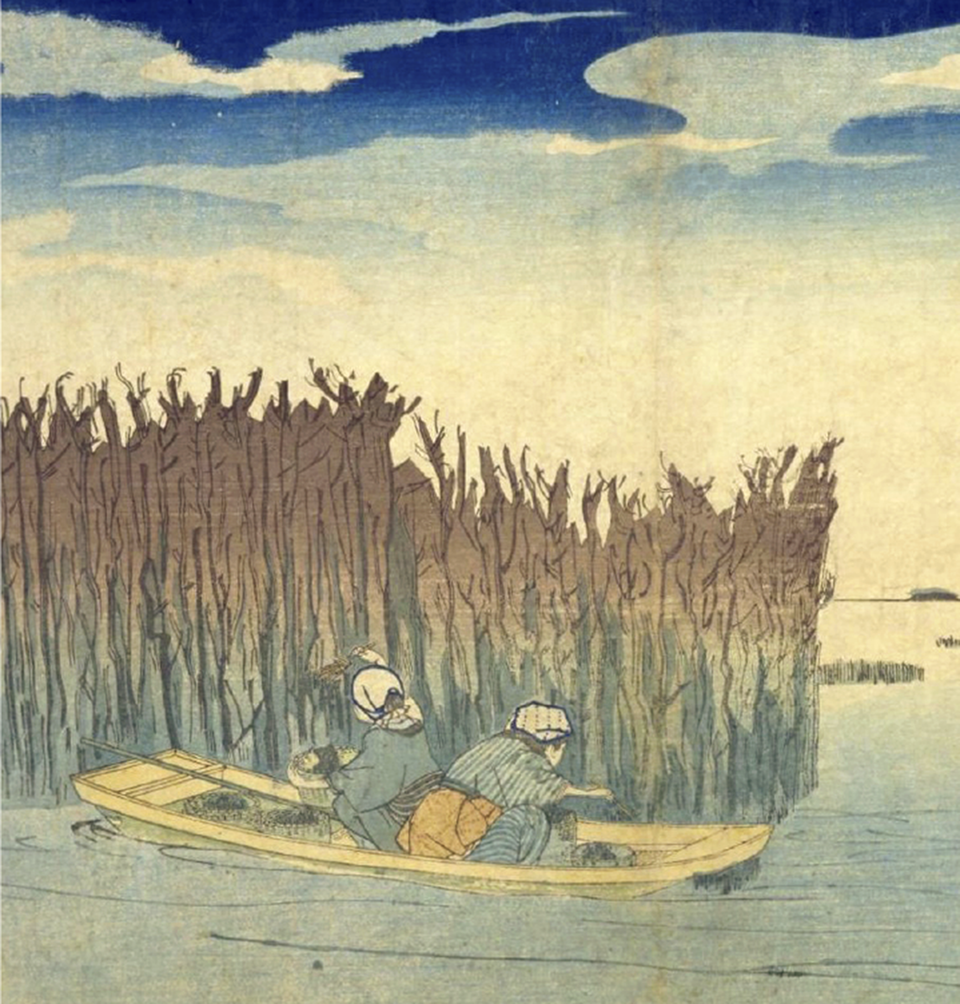

In the Edo period, various regional fishing methods were also developed and passed down as traditional fishing methods, such as "sail seine fishing" in Kasumigaura, where fishermen catch fish by pulling a bag-shaped net while catching wind with a large sail and using its power to slide the boat sideways, and "tub boat fishing", where fisherman use small, highly-maneuverable, tub-shaped boats to collect turban shells, abalone, and other shellfish in Sado Island in the Japan Sea off present-day Niigata Prefecture.

Oyster in the West and Nori in the East

The farming of oysters began in Hiroshima Bay in the early years of the Edo period. Oysters were seen growing naturally on rocks along the shore of the Inland Sea, so someone came up with the idea of tossing rocks into the sea to get oysters to attach themselves to the rocks. Later, the "hibitate method" was developed (in which oysters were farmed by attaching oysters to bamboo or tree branches placed in coastal mud flats). By the mid-Edo period, oysters were being shipped to Osaka in "oyster boats" and it developed a monopoly on sales rights. Oyster boats went to Osaka in autumn, with oystermen mooring their boats at the foot of bridges on the Okawa and Dotonbori rivers to do business on board or in huts scattered along the riverbank.

Also, during the mid-Edo period, in an approach similar to oyster farming, a technique was developed in Omori in Edo Bay to create narrow gaps in shallow water in which seaweed with spores would grow. This cultivated seaweed was sold in front of the Kaminarimon in Asakusa (the "thunder gate," which remains a landmark in present-day Tokyo), and was known as "Asakusa nori."

Seasonal Fishing and Fishing Huts

As the season for each kind of fish approached, villagers would watch and wait in fishing huts for the fish to come in. Villagers who made a living by catching seasonal fish would prepare for the season by splitting their time between rice cultivation and dry-field crops. When a school of fish appears, the entire village went out to catch them.

As fish viewing hut for the mullet fishery still exists in Futo on the Izu Peninsula, and from the Edo period to the 1950s, fishing was done using a net fishing method in which nets were sunken into the water and dragged up when a school of fish arrived over the net. It was such a heroic event as blowing conch shells and using pennants as signals to coordinate their efforts, over 100 villagers would catch fish in this way.

"Scow Houses" for People Living at Sea

In years past, groups of fishermen in Northern Kyushu and in the Seto Inland Sea lived on board ebune, or scow houses. These fishermen fished in small fleets of boats, each consisting of several households, and made their livelihoods by bartering their catch for crops in the farming villages near their anchorages. Although they did not own land or houses, each group had its own headquarters and gathered for New Year's, the summertime bon holidays, and other festivals.

After the Meiji era (1868-1912), these floating fisheries became more settled over time and lost their original form, but the culture of having a boat to sleep in and of couples who fish is still practiced in Nojima (Hiroshima Prefecture) and other places.

Okikamuro: the Island that Sinks During the Bon Holiday

Okikamuro Island in Yamaguchi Prefecture is a small island in the Seto Inland Sea having a circumference of 5 km. It is connected to Suo Oshima by the Okikamuro Bridge (opened in 1983), and had a population of 96 as of 2020 (national census). The island is surrounded by mountains, and the residential area is packed densely into a small flat area by the sea.

The surrounding area has had excellent fishing ground since ancient times, and fishermen thrived on sea bream single hook fishing using the nationally renowned "kamuro hook." Many fishermen moved to the Okikamuro Island, and by the Meiji era, the population exceeded 3,000, and in those days the island was known as Kamuro Senken.

As the population grew, the fishermen of Okikamuro were no longer able to get by with what they could catch in the waters around the island, and they began to go fishing faraway places such as Kyushu, Tsushima, Taiwan. In order to open up new business opportunities, some islanders moved to Hawaii after the first official immigration, and even after the official immigration ended, many islanders continued to go to Hawaii, where they introduced fishing methods and developed fisheries. Tradition has it that the fishing grounds in Hawaii were originally exploited by people from Okikamuro Island.

Okikamuro Island is known as the "island that sinks during the Bon holiday." This means that many people from this small island and their families return home during the summertime Bon holiday to make the island sink. The name was originally given during the Meiji era when men who went fishing in distant places and did not live on the island except for the Bon festival returned to the island en masse.

Fish Finder Invented in Japan

Fish finders, which convert ultrasonic signals bounced off fish into images, were invented in Japan soon after World War II in 1948 and have been in use ever since. At the time, it was only used to identify fish species and size of the fish population. However, in recent years, detection technology has advanced to the point where it is now possible to determine the number and size of fish (quantitative echo sounder).

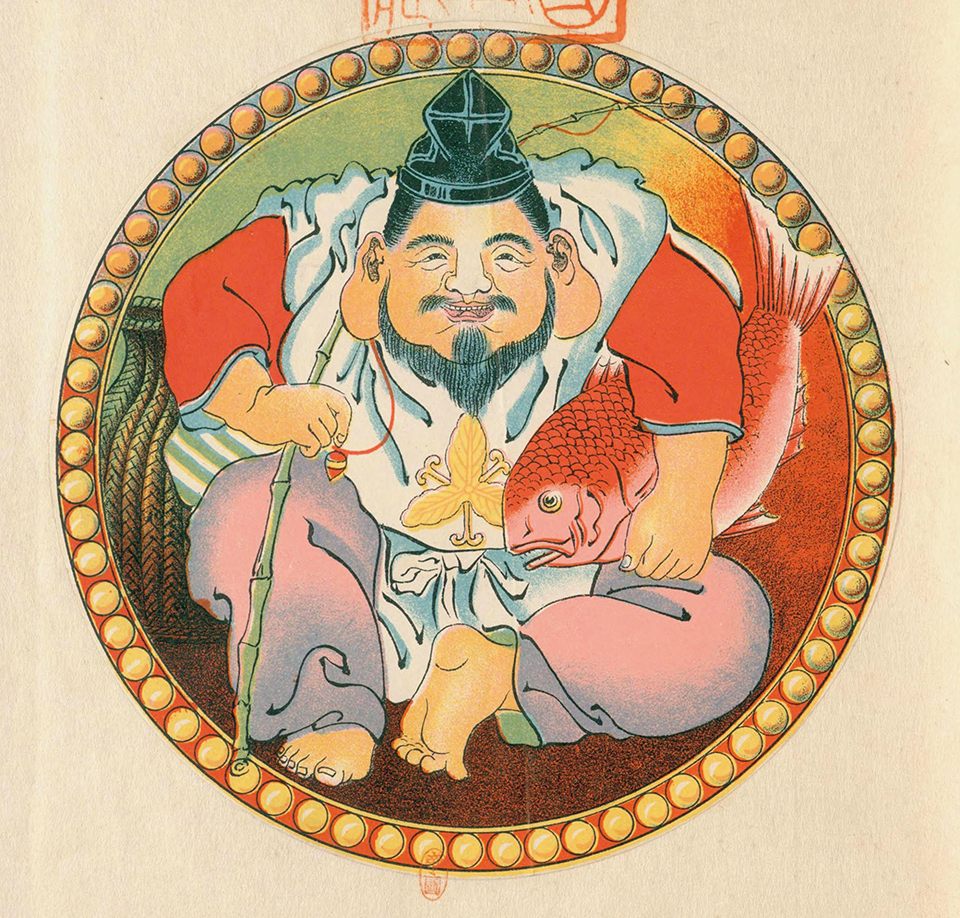

Fishing and Ebisu, the God of Fishing

There are various gods of fishing, such as the Dragon God, the Water God, and Funadama, who are the object of prayers for bountiful catches of fish, and Ebisu, one of the Shichifukujin (Seven Gods of Fortune) is one of them.

Originally, Ebisu, who holds a fishing rod in his right hand and a sea bream in his left, was enshrined on the beach as a yorigami, a god from beyond the sea, but as trade in marine products became more common, Ebisu came to be widely worshipped by merchants as the god of ichi (market) and the god of success in business. Ishizu Shrine and Ishizu-ta Shrine in Sakai of Osaka, are both considered to be the oldest shrines to Ebisu, and according to a legend, they were founded in B.C. Ebisu is also the only one of the Seven Gods of Good Fortune that is actually an ancient Japanese deity.

- The first page

- Previous page

- page 1

- Current page: page 2

- 2 / 2

The issue this article appears

No.63 "Fishery"

Our country is surrounded by the sea. The surrounding area is one of the world's best fishing grounds for a variety of fish and shellfish, and has also cultivated rich food culture. In recent years, however, Japan's fisheries industry has been facing a crisis due to climate change and other factors that have led to a decline in the amount of fish caught in adjacent waters, as well as the diversification of people's dietary habits.

In this issue, we examine the present and future of the fisheries industry with the hope of passing on Japan's unique marine bounty to the next generation. The Obayashi Project envisioned a sustainable fishing ground with low environmental impact, named "Osaka Bay Fish Farm".

(Published in 2024)

-

Gravure: Drawn Fishery and Fish

- View Detail

-

A History of Japan’s Seafood Culture: Focusing on Fermented Fish

SATO Yo-ichiro (Director General, Museum of Natural and Environmental History, Shizuoka; and Emeritus Professor, Research Institute for Humanity and Nature)

- View Detail

-

The Future of Our Oceans, Marine Life, and Fisheries: Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation

MATSUDA Hiroyuki (Emeritus Professor and Specially Appointed Professor, Yokohama National University)

- View Detail

-

What Will Be on the Table in 10 Years?: The Challenge of Fisheries GX

WADA Masaaki (Professor, Future University Hakodate and Director, Marine IT Lab, Future University Hakodate)

- View Detail

-

Fishery This and That

- View Detail

-

OBAYASHI PROJECT

Osaka Bay Fish Farm - Shift from the Clean Sea to the Bountiful Sea

Concept: Obayashi Project Team

- View Detail

-

FUJIMORI Terunobu’s “Origins of Architecture” Series No. 14: Seagrass Houses

FUJIMORI Terunobu

(Architectural historian and architect; Director, Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum; and Emeritus Professor, University of Tokyo) - View Detail

-

Fish Culture This and That

- View Detail