FUJIMORI Terunobu’s “Origins of Architecture” Series No. 14:

Seagrass Houses

FUJIMORI Terunobu

(Architectural historian and architect; Director, Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum; and Emeritus Professor, University of Tokyo)

The only types of architecture I can think of related to the ocean and catching fish are fish markets and lighthouses, however in both cases, there is no particular work among them that has left an especially strong impression on me. Hitting a dead end, I tried chanting "sea, sea, sea, fish, fish, fish," finally stumbling upon something suitable from among the architectural works lingering in the mists of my memory. I will talk about those works here.

The works are houses made with seagrass, which grows in the ocean like a brother to fish. The technique of thatching roofs using grass is called "grass thatching," with grass here referring mainly to Chinese silver grass and common reeds, and sometimes bamboo grass. These grasses are also collectively known as thatch. But I never thought that there would be an example of thatching roofs using "grass of the sea" somewhere in the world.

It was photographer Yoshio Komatsu, creator of Living on Earth, who told me that there are private residences in Denmark with roofs thatched in seagrass. I was also able to visit them myself seven years ago, during a break from the construction of a teahouse in Denmark.

From Copenhagen, I took a train north to the port town of Frederikshavn, the final stop located at the northernmost tip of the country. There, I boarded a small liner and headed east. As we set sail, I could see the outline of a small island on the horizon: it was my destination, Laesoe. However, it did not swell up like the outline of a Japanese island, but was as flat as the horizon. After an hour or so, we arrived on Laesoe, which is now a tourist destination with restaurants, museums, and gift shops all huddled together in a small area.

These seagrass-thatched houses used to be found across the entire island, but now only a dozen or so remain, including some that are vacant. In recent years, efforts have been made to preserve them.

Whether larger residences with courtyards, perhaps belonging to a lord or other influential person, or the tiniest homes, all of the buildings are short and their features small. On entering inside, the interior is compact, on the same scale as a tea ceremony room. It is probable, or rather almost certain, that such small islands in the northern sea were cold and poor.

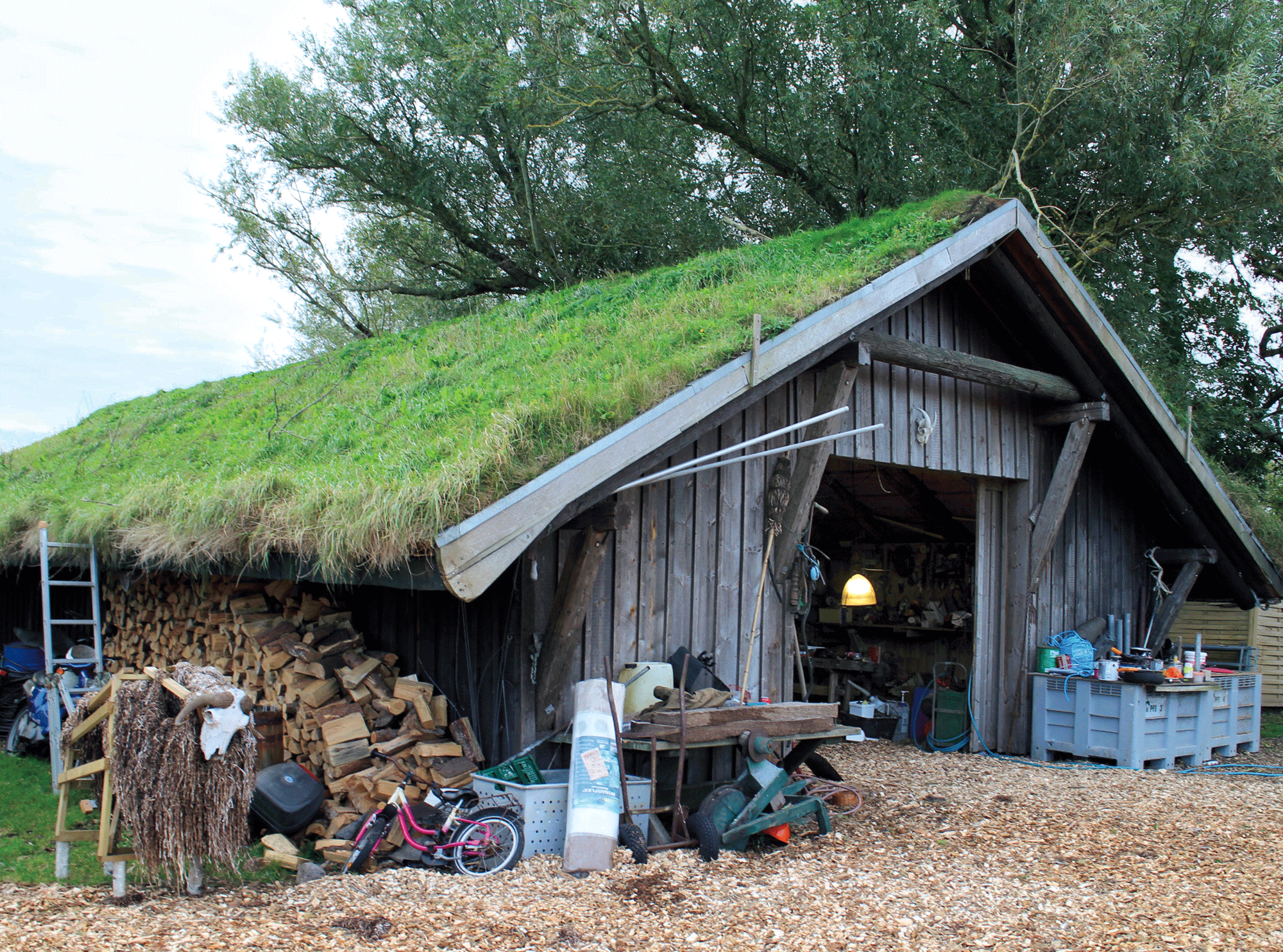

In the midst of all these houses, I came across a building so indomitable that it seemed to stand out from its surroundings and close in upon the viewer. The roof rose up from close to the ground, grass grew on the top, and windows peeked out from the gaps between bulges in the seagrass. It is unlikely that I will again encounter such a beast emerging from the undergrowth; it was an imposing mammoth of a building.

The grass on top is unquestionably a "turf ridge" (shibamune), a tradition of growing plants along the roof ridge that is now only found in parts of Japan, Scandinavia, and France. This tradition is known as being the vestiges of mud-roofed pit houses common in northern Eurasia long ago. The use of mud roofs, that is, roofs covered with mud and planted with grass, allowed Stone Age people to survive in extremely cold climates. In Japan, these mud roofs were used in Jomon-era (14,000 to 300 BC) pit houses. Some have survived in Iceland and Norway, while in Sweden, mud roofs planted with grass on top have been used for log cabins until recently.

This kind of mud roof tradition remained only on the roof ridge, which is referred to as a "turf ridge." I had originally believed that these turf ridges could only be found in two places, Japan and Normandy, France, where the Vikings settled, however I was glad to find that they also survived on the island of Laesoe.

But why would the people on Laesoe go to the trouble of doing such an unusual thing as covering their homes in seagrass, just because their small island was cold and poor? There are trees and grasses growing everywhere you look.

A visit to the small museum solves the mystery. In the past, everything that could be burned was burned, including trees, grasses, and reeds. In the warm summer months, islanders could grow enough barley and legumes to feed themselves, but to purchase ironware, tableware, and textiles from territories outside the island, they had to produce something that could be sold to those territories. That product was salt. Since salt production using seawater requires a final process of boiling down the water in a large kiln, islanders used all kinds of branches, grasses, and reeds they could find on the ground for fuel. What was left was in the ocean.

At first, I doubted whether wakame and kombu, two species of kelp that immediately come to mind when one hears the word "seagrass," could withstand the rain. On the other hand, I considered that as grasses from the ocean, they should be resistant to water, albeit slimy. No, if they were slimy, water would surely run off them well...

I was convinced after seeing the real thing. Despite being a type of seagrass, this particular species is a fine, flat variety that grows as long as Chinese silver grass, and is used after being dried.

The museum also displayed real examples of how to use the seagrass. By first gathering together several dozen dried out one meter-long pieces of seagrass and binding the roots, you can create a bundle for Japanese grass thatching, and this principle is the same for grass thatching all over the world. However, the method for making a bundle of seagrass is very different from that of thatch. While the bundle is extremely fine at the base, new fronds are rolled in one piece after another so that it is thinner at the base, but becomes thicker toward the end. The process is unmistakably similar to the process of twisting cotton fibers into yarn, with dried seagrass fibers working well because they are so strong. I thought that seagrass would be weak because I was associating it with edible kelp varieties such as wakame and kombu, however it is not surprising that there are plants in the ocean with strong fibers like those on land, such as cotton and hemp.

On my way home, I walked along the seashore close to the harbor and found a cluster of these seagrasses in the water. After growing long in the sea, they tear off at the root in winter, then wash up to shore in clumps after being tossed about by the rough waves.

Seagrass houses were once found all along the coast of this strait, but now they only remain on the island of Laesoe. How wonderful that they have survived.

- Current page: page 1

- 1 / 1

FUJIMORI Terunobu

(Architectural historian and architect; Director, Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum; and Emeritus Professor, University of Tokyo)

Born in 1946. Earned a graduate degree from the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Architecture. Fujimori’s major architectural works include Nira (leek) House, Takasugi-an, and the Mosaic Tile Museum, while his published works include Tokyo Project in the Meiji Era (Meiji no tokyo keikaku; Iwanami Shoten), Adventures of an Architectural Detective: Tokyo Edition (Kenchiku tantei no boken tokyo hen; Chikumashobo), and Fujimori Terunobu: How Architecture Works for People (Fujimori terunobu kenchiku ga hito ni hatarakikakeru koto; Heibonsha).

The issue this article appears

No.63 "Fishery"

Our country is surrounded by the sea. The surrounding area is one of the world's best fishing grounds for a variety of fish and shellfish, and has also cultivated rich food culture. In recent years, however, Japan's fisheries industry has been facing a crisis due to climate change and other factors that have led to a decline in the amount of fish caught in adjacent waters, as well as the diversification of people's dietary habits.

In this issue, we examine the present and future of the fisheries industry with the hope of passing on Japan's unique marine bounty to the next generation. The Obayashi Project envisioned a sustainable fishing ground with low environmental impact, named "Osaka Bay Fish Farm".

(Published in 2024)

-

Gravure: Drawn Fishery and Fish

- View Detail

-

A History of Japan’s Seafood Culture: Focusing on Fermented Fish

SATO Yo-ichiro (Director General, Museum of Natural and Environmental History, Shizuoka; and Emeritus Professor, Research Institute for Humanity and Nature)

- View Detail

-

The Future of Our Oceans, Marine Life, and Fisheries: Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation

MATSUDA Hiroyuki (Emeritus Professor and Specially Appointed Professor, Yokohama National University)

- View Detail

-

What Will Be on the Table in 10 Years?: The Challenge of Fisheries GX

WADA Masaaki (Professor, Future University Hakodate and Director, Marine IT Lab, Future University Hakodate)

- View Detail

-

Fishery This and That

- View Detail

-

OBAYASHI PROJECT

Osaka Bay Fish Farm - Shift from the Clean Sea to the Bountiful Sea

Concept: Obayashi Project Team

- View Detail

-

FUJIMORI Terunobu’s “Origins of Architecture” Series No. 14: Seagrass Houses

FUJIMORI Terunobu

(Architectural historian and architect; Director, Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum; and Emeritus Professor, University of Tokyo) - View Detail

-

Fish Culture This and That

- View Detail