A History of Japan's Seafood Culture: Focusing on Fermented Fish

SATO Yo-ichiro (Director General, Museum of Natural and Environmental History, Shizuoka; and Emeritus Professor, Research Institute for Humanity and Nature)

Introduction

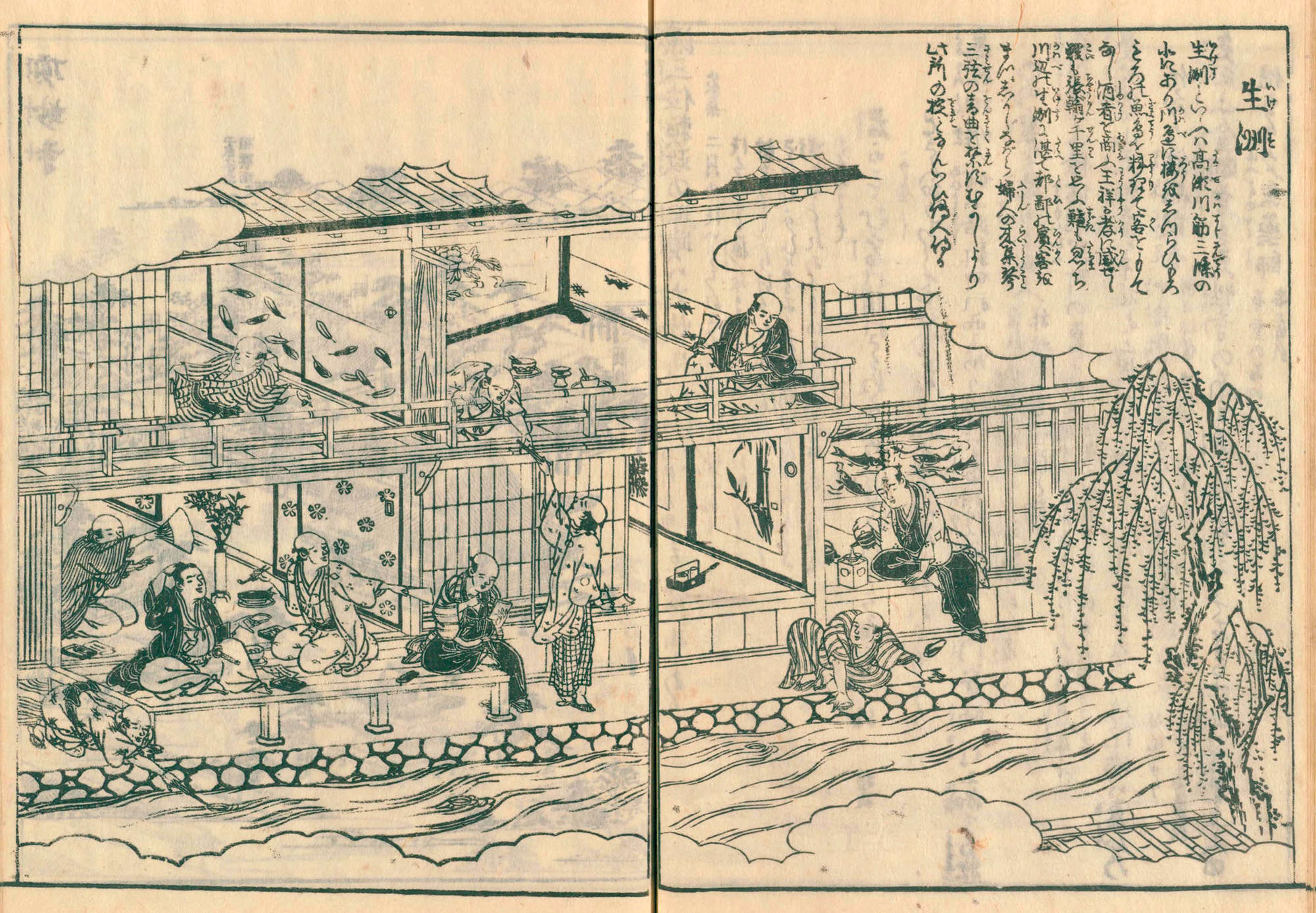

On the Japanese archipelago, large wild mammals were hunted close to extinction during the Jomon period (ca. 14000-2400 B.C.), while herds of domestic livestock such as sheep and cattle were also few in number, save for during the Kofun period (ca. 250-700 A.D.). Consequently, the diet of Japanese people at that time was reliant on fish and shellfish as a source of animal protein. The Kinki region was the capital for over 1,200 years in total from the Fujiwara-kyo period (694-710 A.D.), and with the exception of the Naniwa-no-Miya Palace in present-day Osaka, the capitals were all located inland within the Kyoto and Nara basins. There are still many long-established restaurants in the city of Kyoto specializing in dishes made with freshwater fish from the rivers. At Nishiki Market, a long-running market in the center of the city, there are several shops specializing in river fish alongside those selling fish from the ocean, with the freshest in-season river fish available.

Of course, the capital also had fish from the ocean. Transportation routes from Miketsukuni (Awaji, Wakasa, and Shima; the three regions that supplied the Imperial family and court with regional food) were established early on to bring seafood from the ocean to the capital. However, seafood does not stay fresh for long. In an era where neither refrigeration nor freezing was available, various methods of salting and fermentation were devised that supported the city's fish diet. Here, I would like to examine Japan's seafood culture, with a focus on preserved foods made using fish and shellfish nurtured since ancient times in the Kinki region and other areas across Japan, and which were a staple of Japanese food culture.

Fish Sauce and Funazushi

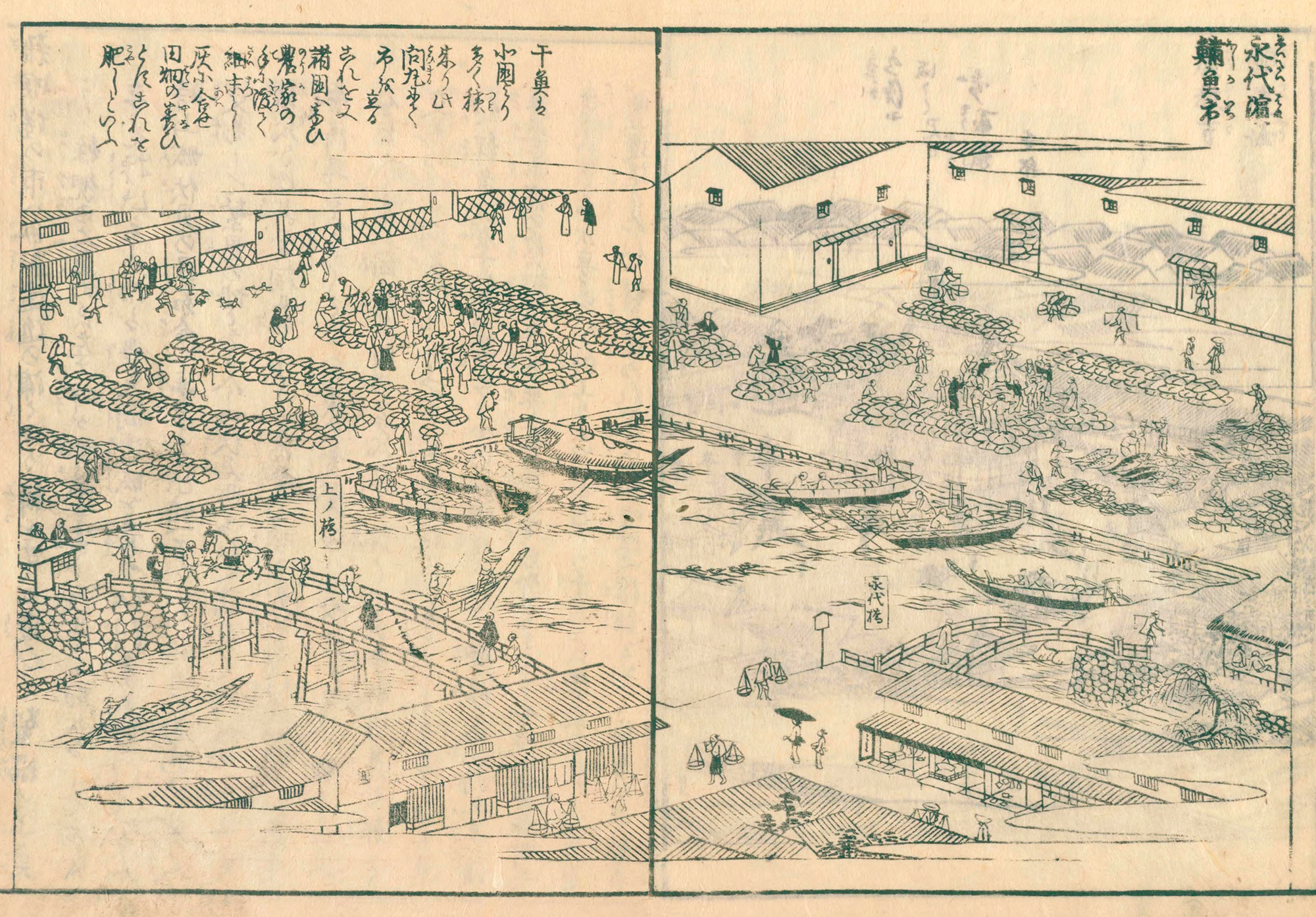

When did fish dishes begin to flourish around the capital? During the 4th and 5th centuries, shortly before the country took shape, Kofun burial mounds were being actively built all over Japan. At this time, the form of the country's food production changed dramatically. Large-scale civil engineering works, including the construction of burial mounds, were being carried out, with large groups of workers recruited for this purpose. Colossal amounts of rice were needed to feed them. Accordingly, huge irrigation facilities were built to supply water to the rice fields. Many irrigation ponds were built in the southern part of the Osaka Plain from this time up until the Edo period (1603-1868). As the number of rice fields and irrigation facilities increased, the rice field ecosystem grew larger. The fish that eventually populated these rice field ecosystems became a source of protein. It seems that we can see the origin of "rice and fish in a package," the foundation of Japanese cuisine, from this time.

But how was the fish prepared? One method seems to have been fermentation in the loosest sense of the word. When fish or other flesh is covered with about 20% salt by weight and left in a vat or similar, enzymes that break down protein in the muscle work to dissolve the meat and bones into a thick paste. The liquid strained or filtered out from this is fish sauce. The production process today is unchanged from the past. Fish sauce is still being produced in many places across the world. In Japan, the most famous are ishiru and ishiri from the Noto Peninsula and shottsuru (Hatahata soy sauce) from Akita. Overseas, the best known are nước mắm from Vietnam and nam pla from Thailand, as well as garum from Italy.

Narezushi is a dish prepared by combining fish and salt with cooked grains. It is believed to have originated in the humid, mountainous regions from southern China to Mainland Southeast Asia. The dish seems to have made its way to Japan during ancient times. Funazushi, a similar dish that is still served in places around Lake Biwa, is said to be a remnant of this.

In the Nanki region, which extends across both Mie and Wakayama Prefectures, you can find narezushi made with pacific saury. Along with pacific saury, barracuda, mackerel, and ayu sweetfish are also used. However, narezushi is rarely kept for as long as six months like funazushi, and is usually eaten within two to three weeks. I will come back to this later on. Note that bo-zushi (stick-shaped sushi topped with strips of fish) used to be made with pacific saury in the Nanki region in Wakayama, which is located in the southern part of Kii Peninsula below the Kumano region. The dish is a type of haya-zushi, or "fast sushi," that does not undergo lactic acid fermentation like narezushi. Instead, the rice is vinegared with rice vinegar or yuzu juice and eaten within about 10 days (during winter).

Salted Fish: Focusing on Mackerel

Another method that has long been commonly used for preserving fish is salting. It should be stated that since salt is also used in the fermentation process mentioned above, the salting process referred to here is separate from salting in fermentation. Various types of fish are used, but here I would like to write about sabazushi, a sushi dish from the Kinki region.

Sabazushi is made by adding vinegared rice to salted mackerel lightly marinated with vinegar It is a preserved food that combines the methods of salt and vinegar fermentation. Variations on this dish are known in regions all across Japan. The endless varieties include sugatazushi, where the mackerel is served whole with the head and tail attached, sushi covered with kombu (edible kelp), and even sushi made with seared mackerel.

Moreover, there is no single way of writing the name sabazushi, which appears in both hiragana, phonetic characters, and kanji combined in several different ways. One of the cities where the name sabazushi was well-known is Kyoto. Many sushi restaurants in the city serve sabazushi, including Izuu, which was established in the Gion area in 1781. There are variations even among Japanese restaurants, with some that serve it as a vinegar dish, and some that serve it as a rice dish. There are also several exclusively take out restaurants with a number of sales locations.

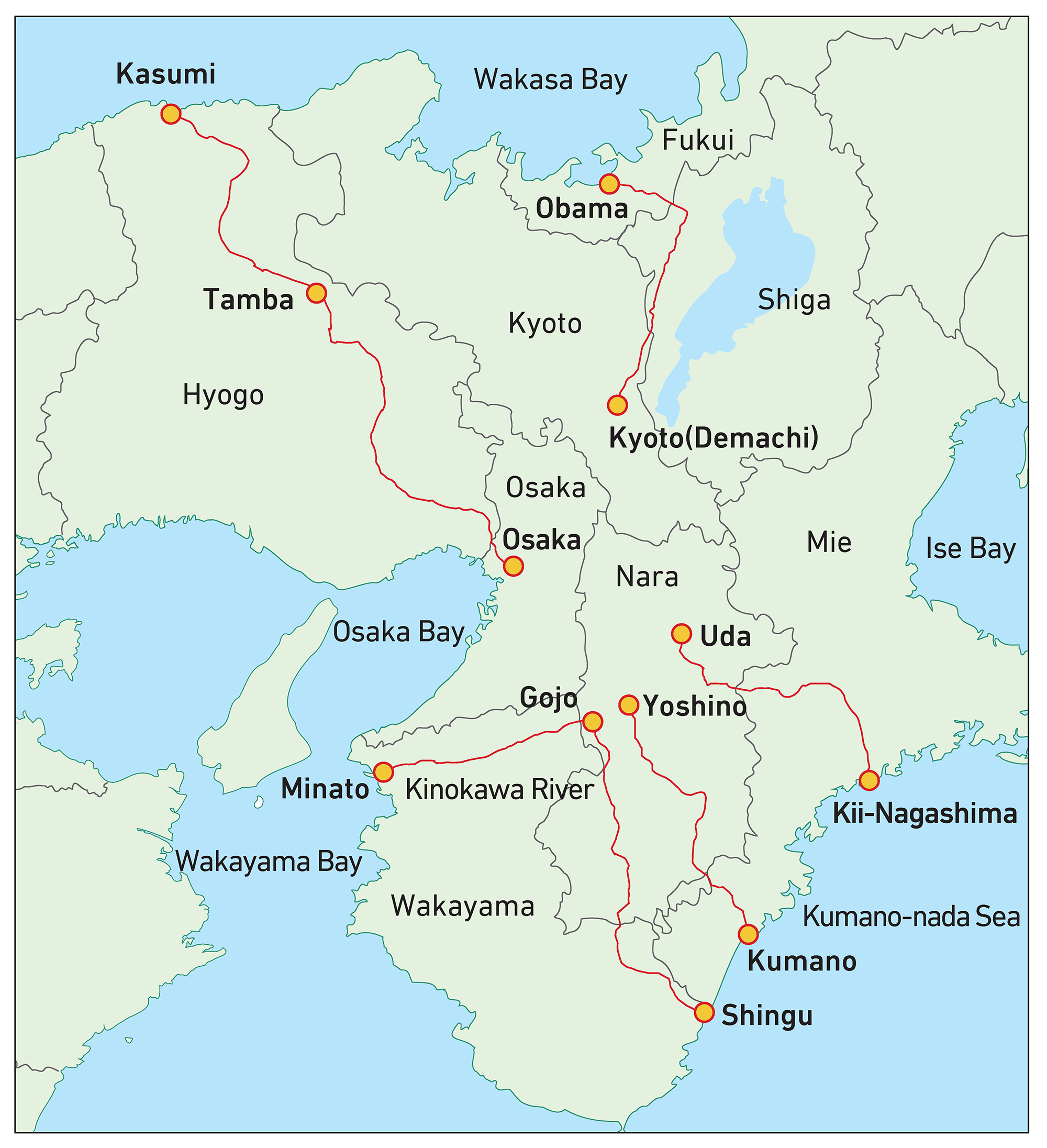

The mackerel used in Kyoto's sabazushi is caught in the city of Obama, Fukui Prefecture. The fish is immediately filleted on the beach, lightly salted, and transported to Kyoto along the Saba Kaido (meaning "mackerel road"). From Obama, the Saba Kaido crosses the mountains into Shiga Prefecture, then passes over a mountain pass into Sakyo Ward, Kyoto City.

The end point of the Saba Kaido is Demachi, the convergence point of the Kamo and Takano rivers upstream of the Kamo River, which cuts through the city of Kyoto from north to south. The Saba Kaido follows the Takano River downstream. In Kyoto, sabazushi is a specialty food served on special occasions. When an order comes in from the teahouse at Izuu, the sushi is served on a koimari porcelain plate and brought in by an okamochi, a carrying box coated in Wajima-nuri lacquer.

Osaka has its own type of sabazushi called battera. I cannot see a clear difference between these two dishes, however, if pushed, I would say that battera is often made into boxed sushi, while sabazushi is normally rolled using a cloth or bamboo rolling mat. Both are supported by a strong sense of hometown pride, so be careful not to call them by the wrong name or you will be scolded.

- Current page: page 1

- page 2

- 1 / 2

- Next page

- The last page

SATO Yo-ichiro (Director General, Museum of Natural and Environmental History, Shizuoka; and Emeritus Professor, Research Institute for Humanity and Nature)

Born in 1952. Earned a graduate degree from Kyoto University’s Graduate School of Agriculture. Doctor of agriculture specializing in botanical genetics. Sato was a key player in the creation of Japanese food studies, serving as the first chairperson of the Society of Japanese Food Studies. His published works include What DNA Can Tell Us About Rice Farming Civilization (DNA ga kataru inasaku bunmei ; NHK Publishing), A Human History of Food (Shoku no jinrui-shi ; Chuokoron-Shinsha), and A Cultural History of Japanese Food (Washoku no bunka-shi ; Heibonsha).

The issue this article appears

No.63 "Fishery"

Our country is surrounded by the sea. The surrounding area is one of the world's best fishing grounds for a variety of fish and shellfish, and has also cultivated rich food culture. In recent years, however, Japan's fisheries industry has been facing a crisis due to climate change and other factors that have led to a decline in the amount of fish caught in adjacent waters, as well as the diversification of people's dietary habits.

In this issue, we examine the present and future of the fisheries industry with the hope of passing on Japan's unique marine bounty to the next generation. The Obayashi Project envisioned a sustainable fishing ground with low environmental impact, named "Osaka Bay Fish Farm".

(Published in 2024)

-

Gravure: Drawn Fishery and Fish

- View Detail

-

A History of Japan’s Seafood Culture: Focusing on Fermented Fish

SATO Yo-ichiro (Director General, Museum of Natural and Environmental History, Shizuoka; and Emeritus Professor, Research Institute for Humanity and Nature)

- View Detail

-

The Future of Our Oceans, Marine Life, and Fisheries: Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation

MATSUDA Hiroyuki (Emeritus Professor and Specially Appointed Professor, Yokohama National University)

- View Detail

-

What Will Be on the Table in 10 Years?: The Challenge of Fisheries GX

WADA Masaaki (Professor, Future University Hakodate and Director, Marine IT Lab, Future University Hakodate)

- View Detail

-

Fishery This and That

- View Detail

-

OBAYASHI PROJECT

Osaka Bay Fish Farm - Shift from the Clean Sea to the Bountiful Sea

Concept: Obayashi Project Team

- View Detail

-

FUJIMORI Terunobu’s “Origins of Architecture” Series No. 14: Seagrass Houses

FUJIMORI Terunobu

(Architectural historian and architect; Director, Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum; and Emeritus Professor, University of Tokyo) - View Detail

-

Fish Culture This and That

- View Detail