Fish Culture This and That

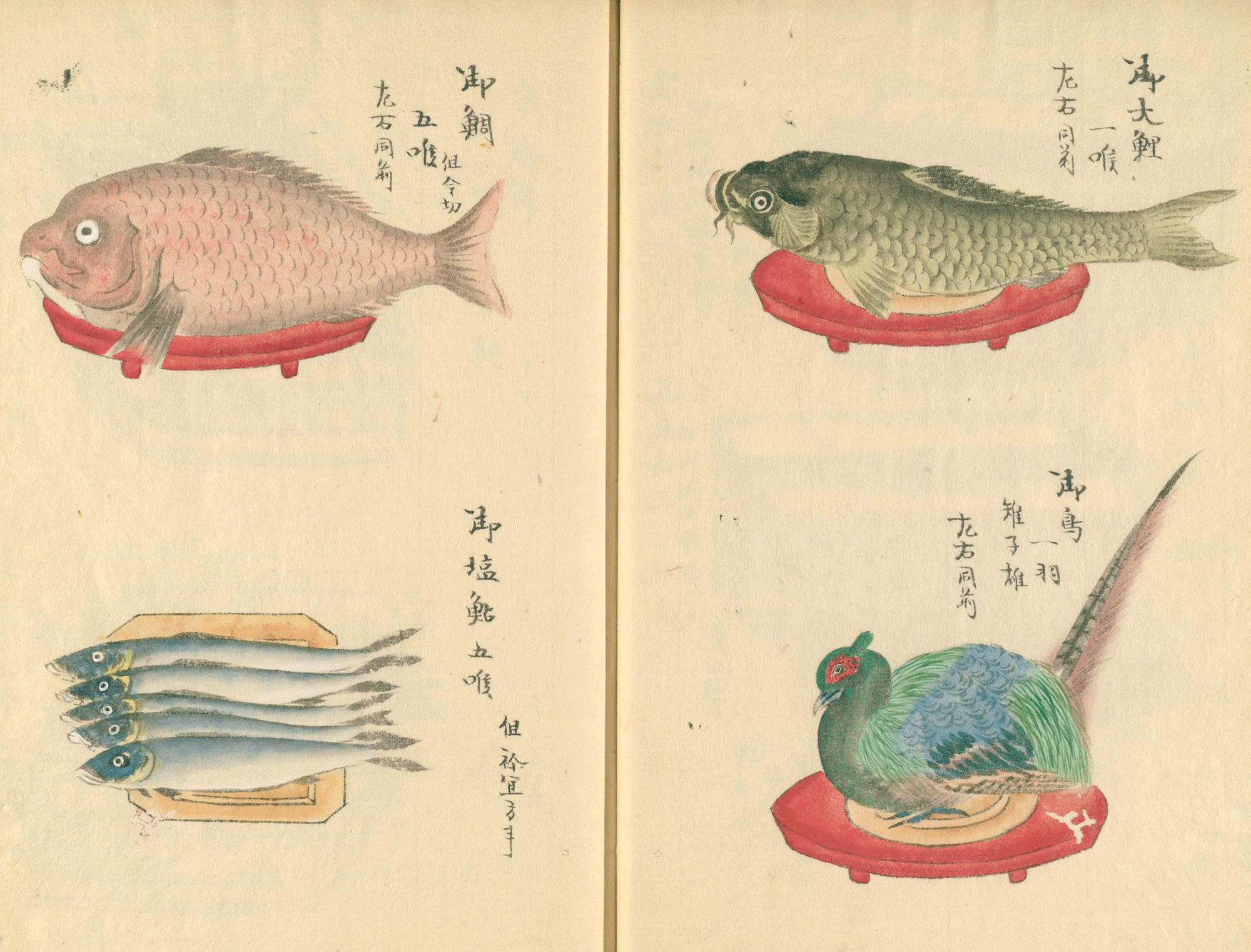

Fish as an Offering

Fish is an important food for the Japanese people, and has been offered as a shinsen (offering to the gods) since ancient times. Abalone, squid, bonito, salmon, and other seafood, as well as kelp and other seaweed are listed in the "Engishiki" (detailed regulations for the enforcement of the Ritsuryo System) as offerings to the emperor at the Daijosai (the ceremony of the emperor's enthronement), in addition to sake, rice, beans, and fruit. Abalone, sea bream, kelp, and katsuobushi (dried bonito) have also been offered as food for the gods at the Ise Jingu Shrine for centuries.

The custom of serving fish from the sea to those who helped rice planting was observed in many parts of Japan, and such fish were called taue-uo (rice-planting fish.)

The New Year's dish tazukuri is derived from the custom which, originally, the sardine dish was served at rice planting time and the fact dried sardines were used as fertilizer, symbolizing a bountiful harvest.

In Buddhism, a small amount of rice to be served before a meal is called saba in order to be prepared for hungry ghosts (spirits of the dead who suffer from eternal hunger because of their evil during their lifetime) and Hariti. The custom mainly in Kansai region of giving salted mackerel and sashisaba (two salted mackerels split down the back, with the head pierced) as gifts to parents and masters with wish for their long-life in Obon or new year seasons was originated from saba.

The Japanese and Eel

I want to tell Ishimaro,

that it is good for summer weight loss,

to catch and eat eel

By Otomo no Yakamochi, in Manyoshu

Eel has figured in the diets of the Japanese people as nourishing meal for so long that a poem recommending that people eat eel as a way to prevent summertime weight loss was included in Manyoshu (compiled in the Nara period (710-794)).

Eel has customarily been eaten on Doyou no ushi (the Midsummer Day of the Ox) since the mid-Edo period. One theory about the custom's origin that it came about the story when the inventor and polymath HIRAGA Gennai was consulted by an eel shop whose sales were declining. HIRAGA advised the shop to place a sign in front saying, "Today is the Midsummer Day of the Ox", and this strategy worked to make the shop prospered.

Today's way of cooking eel goes back to the Edo period. The difference is that in the Kanto region (Edo/Tokyo, etc.), the eel is split along the back and steamed before grilling, while in the Kansai region (Osaka, Kyoto, etc.), the eel is split along the belly and grilled without steaming. It is said that the fat content of eels caught in the suburbs of Edo was higher, so the excess fat was removed by steaming, resulting in a soft texture in Kanto while Kansai-style yields a dish with more savory finish.

Developing a Culture of Dashi (broth)

In the early Edo period, a merchant named KAWAMURA Zuiken established the Nishimawari koro (Western Sea Route) and started the Kitamae-bune cargo shipping service which sailed from the Sea of Japan to Shimonoseki in Western Honshu, then into the Inland Sea and on to Osaka. This route brought large quantities of high-quality kombu (edible kelp) from Hokkaido to Osaka.

Before being transported to Edo, kelp was stored in Osaka, which could be described as the nation's kitchen, with the very best kelp consumed mainly in Osaka and Kyoto. It is also said that the relative softness of the water in the Kansai region made it suitable for extracting dashi using kombu. On the other hand, the hardness of the water in the Kanto region made it difficult to prepare a kombu dashi, which is why dried bonito flakes (katsuobushi) became popular in the Kanto region. Some say that this is the origin of the distinction of dashi (broth) culture between the Kanto region, which mainly uses bonito, and the Kansai region, which mainly uses kelp.

Dried bonito has been produced in Japan since ancient times, and is described in the 8th century Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters) as katauo (hard fish). In earlier times, production method was simply boiling and drying, and was mainly used as a seasoning.

Early in the Edo period, KADOYA Jintaro, a fisherman from Kishu, a region well-known for bonito, moved to Tosa and devised a production technique used today. By repeatedly roasting, drying, fermenting, and sun-drying, KADOYA was able to produce high-quality dried bonito flakes with increased flavor and shelf life, which were then used as dashi.

Furthermore, around the same time, "awase-dashi" (broth made of a combination of kelp and dried bonito flakes) was created to bring out more flavor, and that became the base of Japanese food culture primarily in Kyoto.

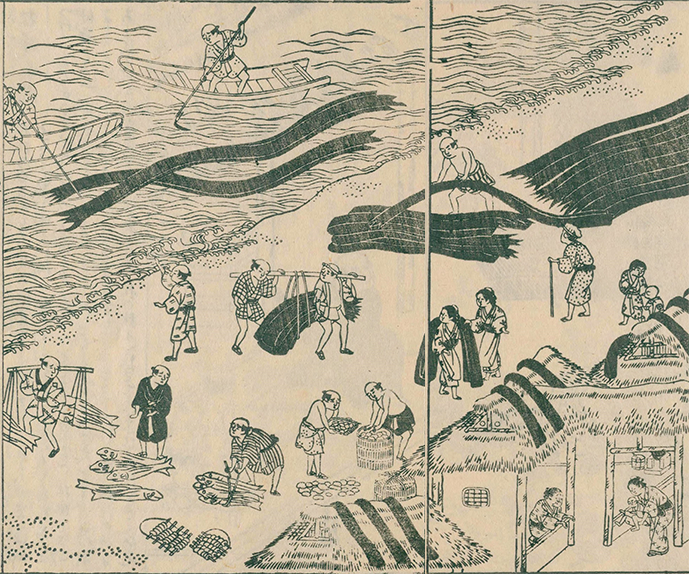

Since kombu and katsuobushi were expensive, ordinary people began to make soup stock by drying sardines (niboshi), which were caught in large quantities.

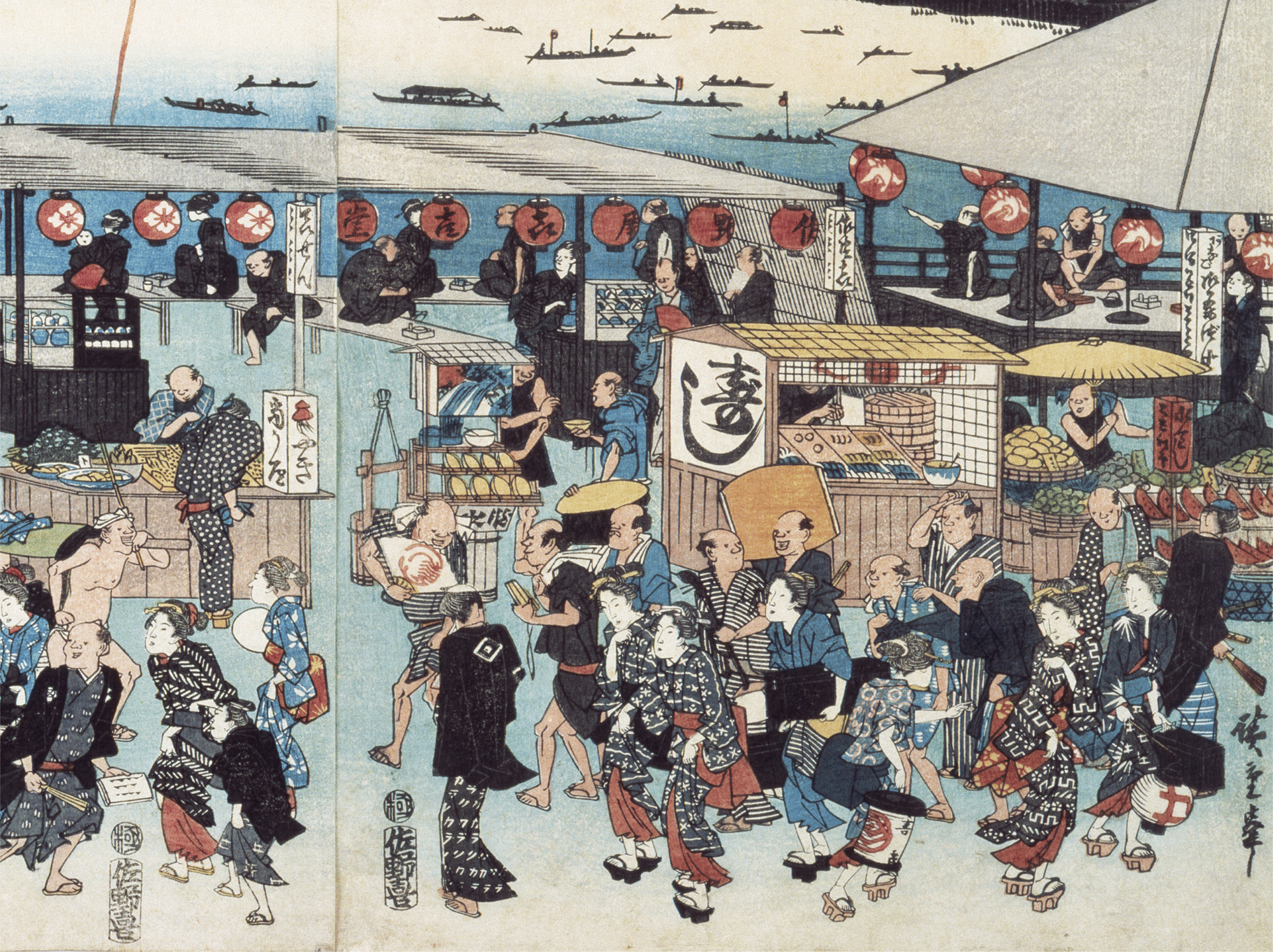

Edomae Fish and Food Stand

The "Edomae Sea" stretching south from Edo Castle was rich in seafood, with flounder, whitebait, clams, and shrimp among its specialties.

Nigirizushi, or nigiri sushi consisting of raw fish served on vinegared rice, originated in the late Edo period. The town was crowded with food stands of "Edomae Sushi", tempura, glaze-grilled eel, and other dishes, offering "Edomae Fishes", and Japanese food culture was developed from those food stands.

- Current page: page 1

- page 2

- 1 / 2

- Next page

- The last page

The issue this article appears

No.63 "Fishery"

Our country is surrounded by the sea. The surrounding area is one of the world's best fishing grounds for a variety of fish and shellfish, and has also cultivated rich food culture. In recent years, however, Japan's fisheries industry has been facing a crisis due to climate change and other factors that have led to a decline in the amount of fish caught in adjacent waters, as well as the diversification of people's dietary habits.

In this issue, we examine the present and future of the fisheries industry with the hope of passing on Japan's unique marine bounty to the next generation. The Obayashi Project envisioned a sustainable fishing ground with low environmental impact, named "Osaka Bay Fish Farm".

(Published in 2024)

-

Gravure: Drawn Fishery and Fish

- View Detail

-

A History of Japan’s Seafood Culture: Focusing on Fermented Fish

SATO Yo-ichiro (Director General, Museum of Natural and Environmental History, Shizuoka; and Emeritus Professor, Research Institute for Humanity and Nature)

- View Detail

-

The Future of Our Oceans, Marine Life, and Fisheries: Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation

MATSUDA Hiroyuki (Emeritus Professor and Specially Appointed Professor, Yokohama National University)

- View Detail

-

What Will Be on the Table in 10 Years?: The Challenge of Fisheries GX

WADA Masaaki (Professor, Future University Hakodate and Director, Marine IT Lab, Future University Hakodate)

- View Detail

-

Fishery This and That

- View Detail

-

OBAYASHI PROJECT

Osaka Bay Fish Farm - Shift from the Clean Sea to the Bountiful Sea

Concept: Obayashi Project Team

- View Detail

-

FUJIMORI Terunobu’s “Origins of Architecture” Series No. 14: Seagrass Houses

FUJIMORI Terunobu

(Architectural historian and architect; Director, Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum; and Emeritus Professor, University of Tokyo) - View Detail

-

Fish Culture This and That

- View Detail