What Will Be on the Table in 10 Years?: The Challenge of Fisheries GX

WADA Masaaki (Professor, Future University Hakodate and Director, Marine IT Lab, Future University Hakodate)

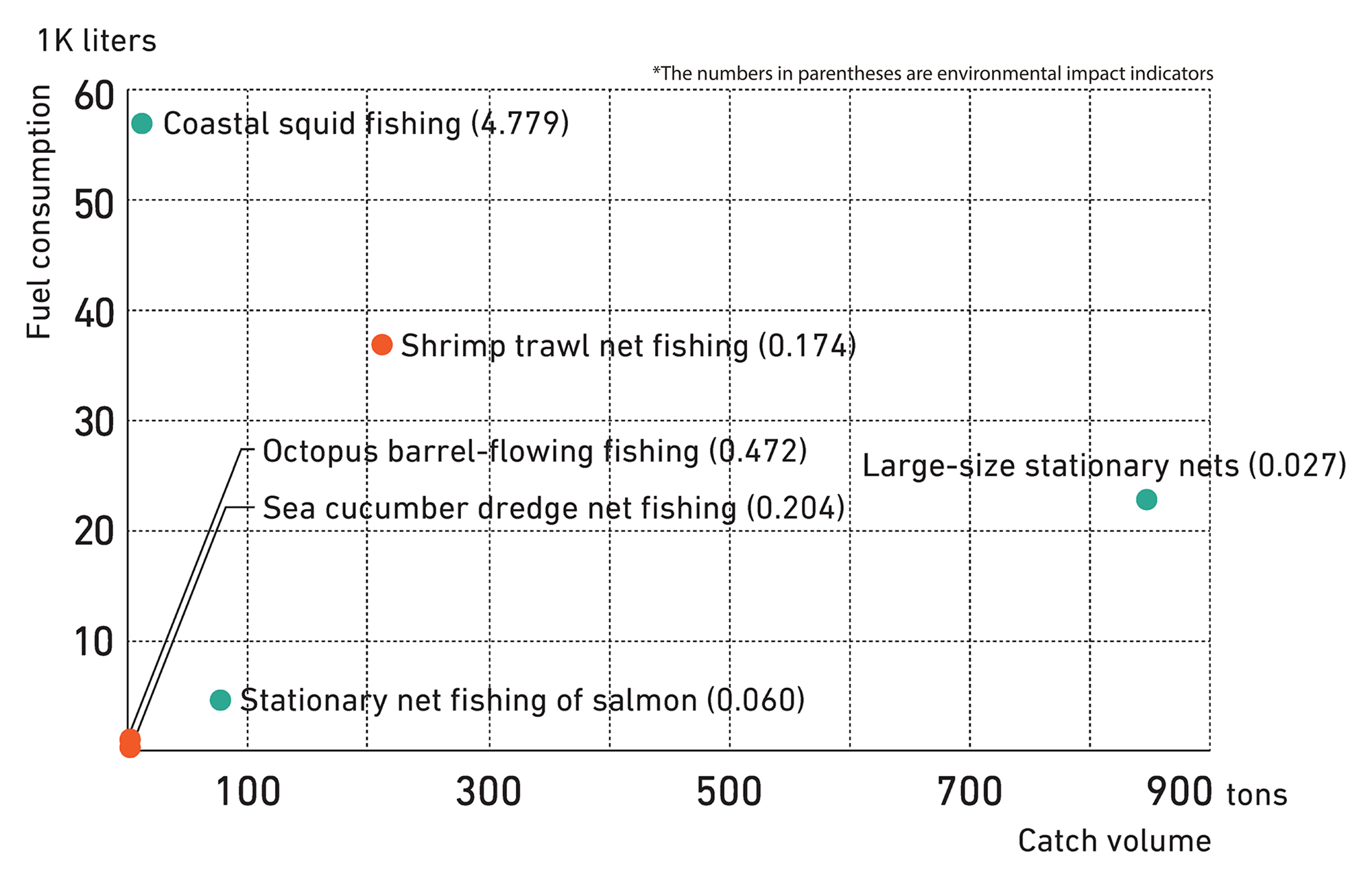

Environmental Impact Indicators by Fishing Method

Squid in June was 12.455. Do you know what this number means? Hakodate is associated with squid and night views. The fishing lights for luring fish floating beneath Mount Hakodate have become a familiar sight in Hakodate during fall. According to statistics from Hakodate City, the volume of squid caught by the Hakodate City Fisheries Cooperative Association in 2021 was 204 tons, a new record for the lowest catch since 2000. Meanwhile, the highest catch volume since 2000 was 1,980 tons in 2007, indicating a drop of as much as 90%. Squid fishing is a method of catching squid by gathering them together using fishing lights. To be more precise, fishing lights shine brightly out to sea, causing squid, who dislike bright light, to attempt to escape to darker places. The dark places are underneath the fishing boats, which is where the light of the fishing lights cannot reach, and as a result, squid fleeing from the light gather under the boats. Fishing lights are bright enough to be captured by satellites due to the clear contrast they create out at sea. As an aside, squid fishing boats do not go out on nights with a full moon, as the fishing lights will not be effective.

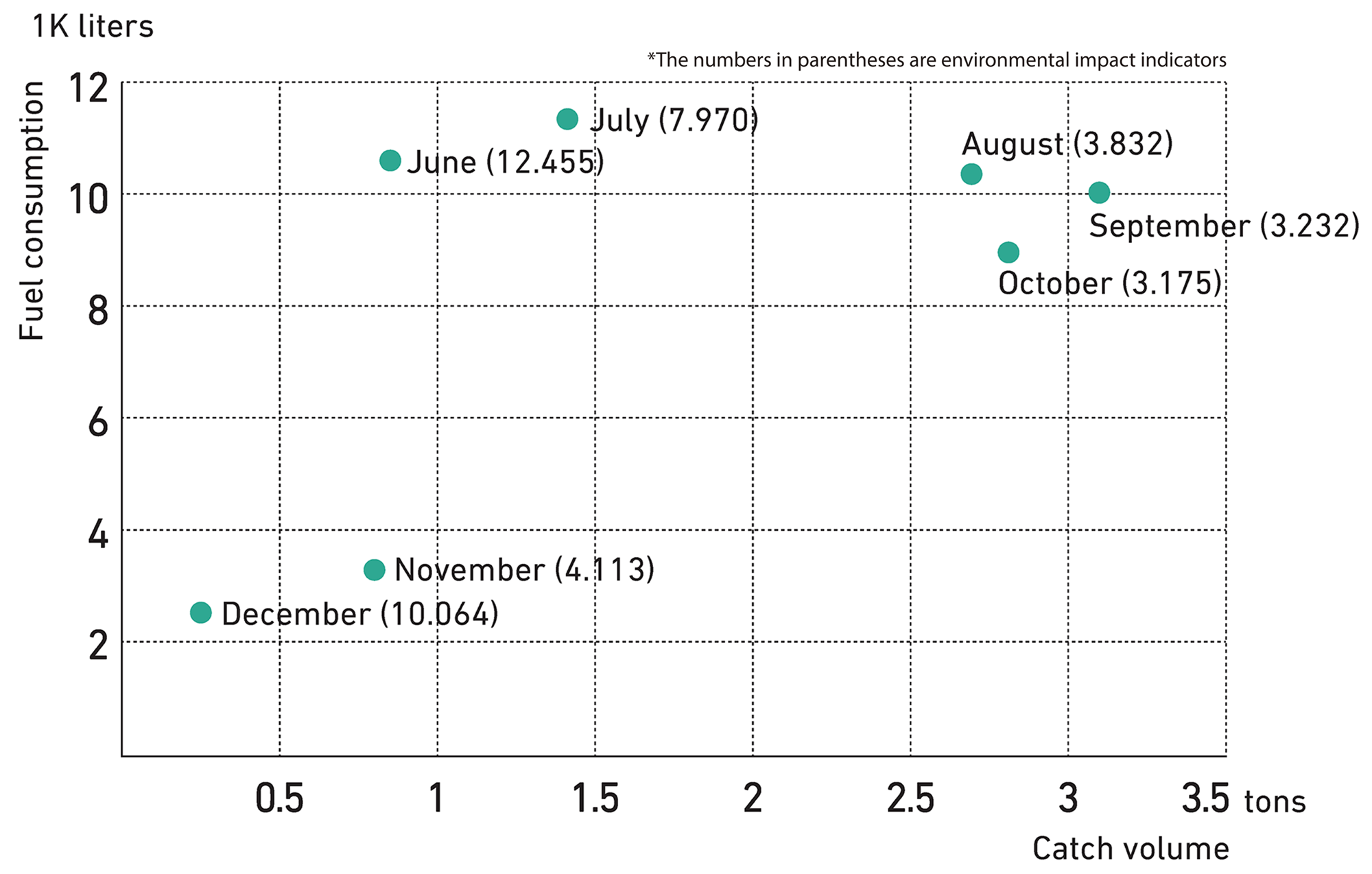

Let's get back to the matter of environmental impact. Although fishing lights may look like a single entity, squid fishing boats are equipped with about 50 three-kilowatt lights for gathering squid, and when lit for 24 hours, the amount of electricity used by the fishing lights is equivalent to the annual electricity consumption of an entire household. The unit for the above-given figure of 12.455 is liters/kilogram. It refers to the amount of fuel oil used by one squid fishing boat to catch one kilogram of squid in June 2021. Since squid completes its lifespan over one year, squid in June are still small, with eight squid weighing about one kilogram. This means that about 1.5 liters of fuel oil is used to catch a single approx. 120gram squid. When served on the dinner table, transparent and fresh locally produced squid sashimi may look beautiful, but can it really be considered an environmentally friendly food?

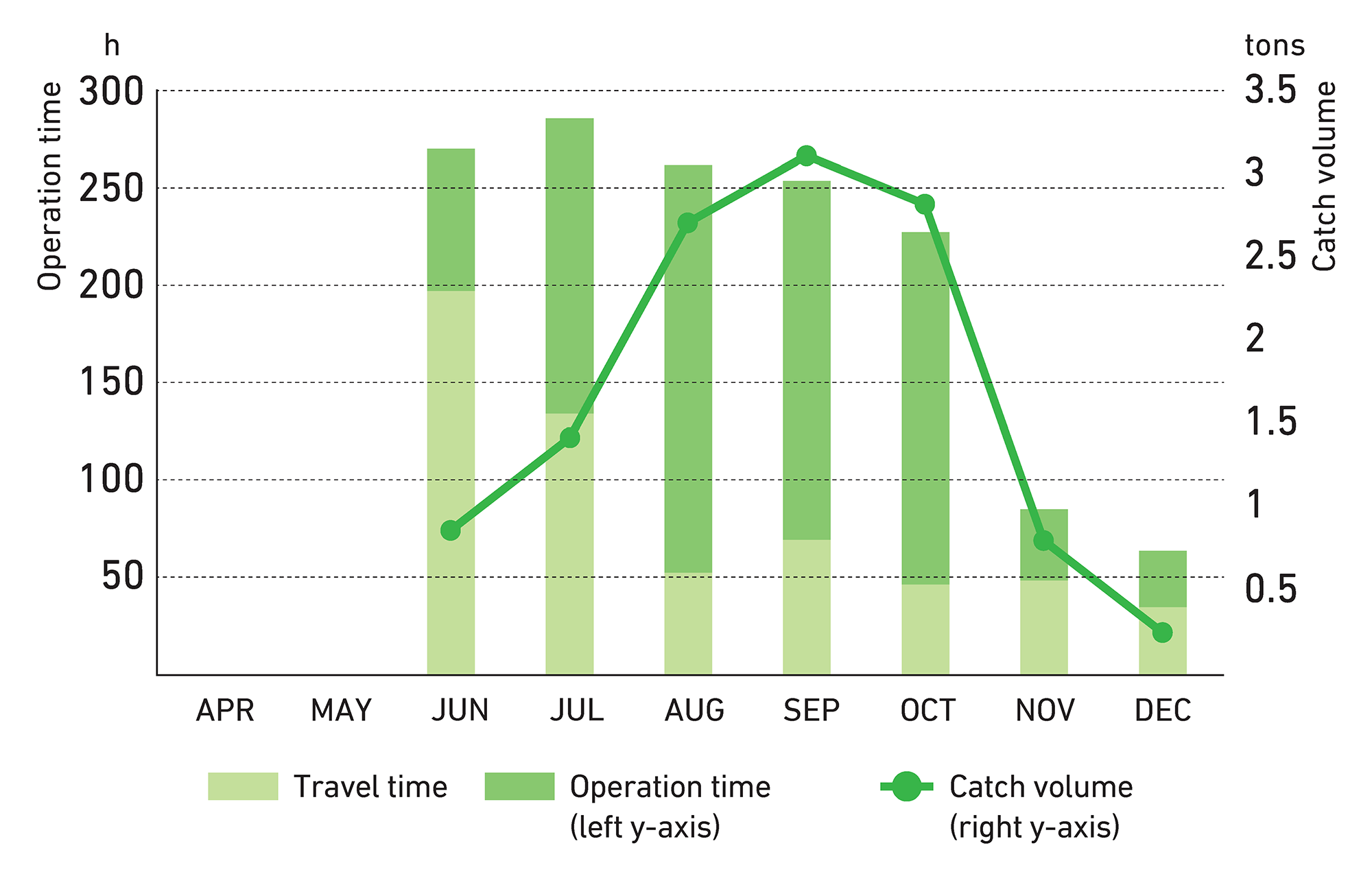

I checked the fishing grounds by month using data from 2021 to try calculating the amount of fuel oil used to catch one kilogram of squid as an environmental impact indicator. Squid are born in the East China Sea between fall and winter. Shoals born in fall grow up as they move northward across the Sea of Japan about one month behind the "cherry blossom front." Although the ban on squid fishing in Hakodate is lifted in June, the water temperature off the coast of Hakodate in June is lower than the optimal temperature for squid, therefore the fishing grounds form in the western part of the Tsugaru Peninsula, far away from Hakodate. Accordingly, it took 12.3 hours to travel both way to the fishing grounds, with the squid-fishing operation taking 4.5 hours. From summer onward, the fishing grounds form off the coast of Hakodate, and in October, travel time was 2.8 hours and working time was 11.3 hours, resulting in an environmental impact indicator of 3.175. In October, four squid weigh about one kilogram, so this means that about one liter of fuel oil was used to catch a single approx. 250gram squid.

[Environmental Impact Indicators By Fishing Method (2021)]

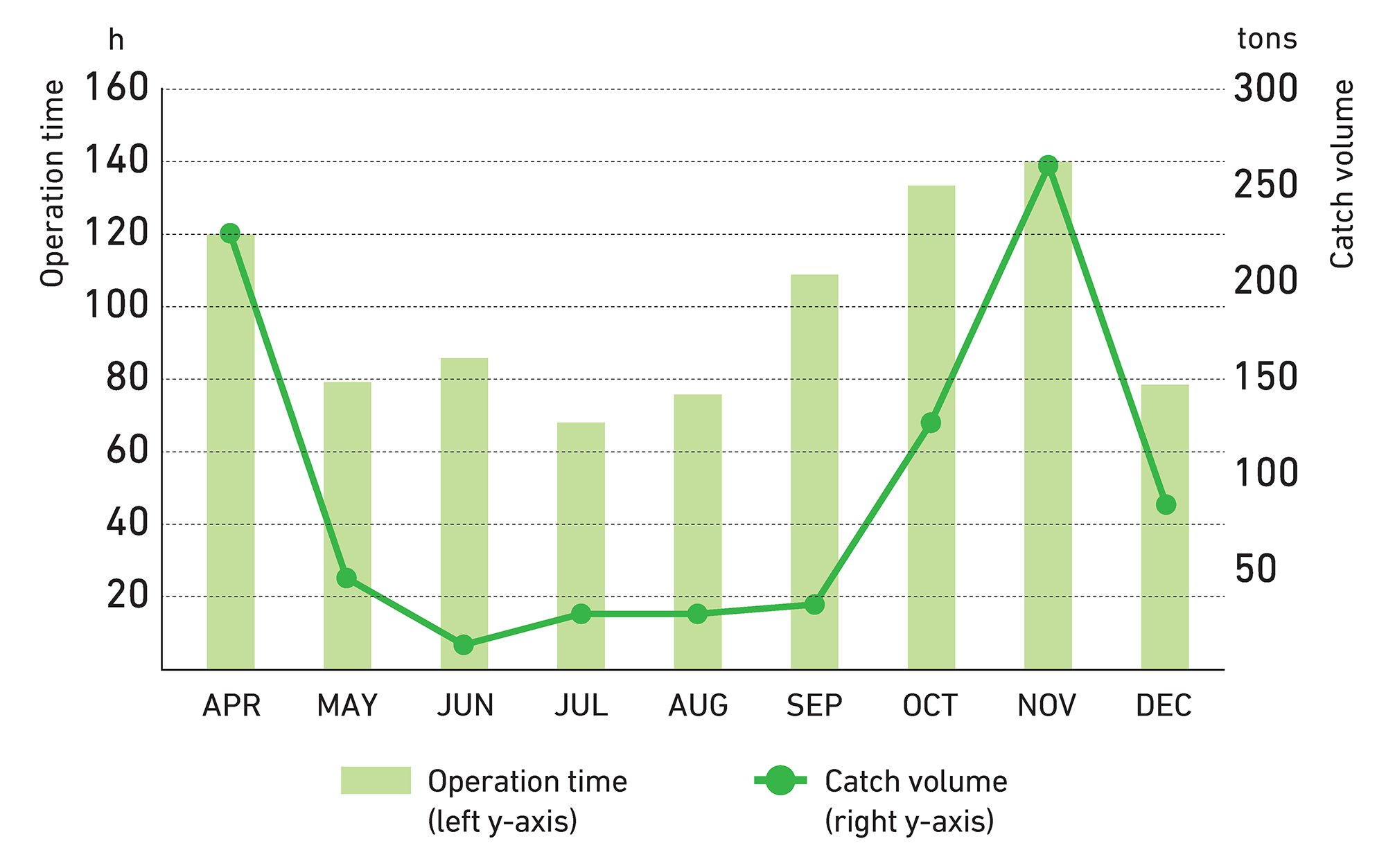

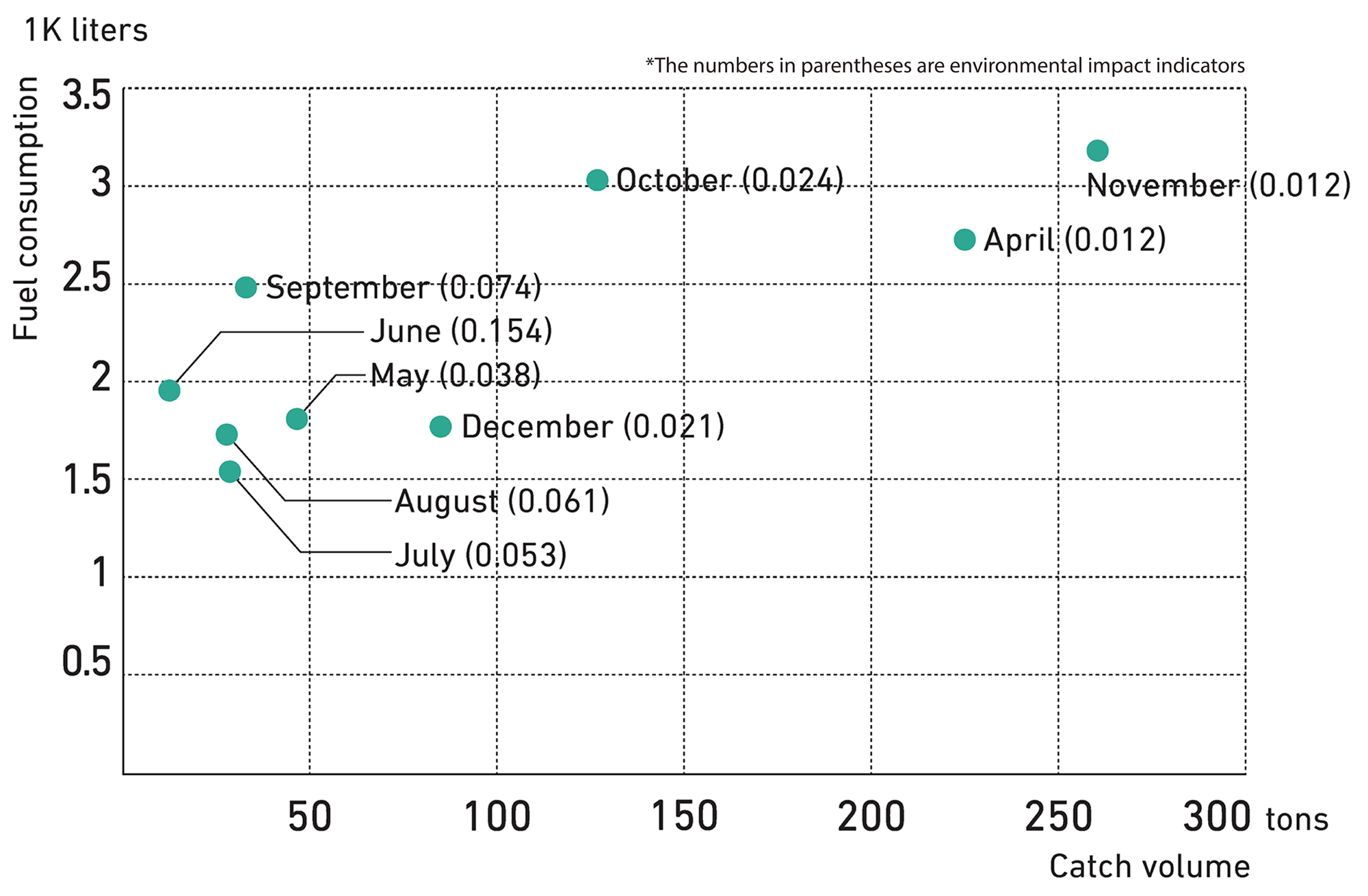

For comparison, I tried calculating the environmental impact indicator of stationary nets. Stationary nets are a fishing method accounting for about 40% of coastal wild-catch fishing catches nationwide. In Hakodate, stationary nets are used to catch about 100 species of fish, including tuna, Japanese amberjack, mackerel, and squid. Stationary nets in Hakodate are not operated during the three-month period between January and March to protect resources; operations typically begin in April. If we try calculating the amount of fuel oil used to catch one kilogram of fish in one kato(*2) of stationary nets in 2021 by month, the environmental impact indicator was smallest in April and November at 0.012 and largest in June at 0.154. Further, the monthly catch of squid by one kato of stationary nets in October 2021 was almost the same as the annual catch of a single squid fishing boat. The environmental impact indicator of the stationary nets in October 2021 was 0.024, which shows a difference of over 100fold between fishing methods, even for the same Hakodate squid. When calculating environmental impact indicators in 2021 across the entire year, the indicator for Hakodate squid fishing was 4.779, while the indicator for stationary net fishing was 0.027. For reference, indicators for other fishing methods were as follows: stationary net fishing of salmon in Rumoi was 0.060, shrimp trawl net(*3) fishing was 0.174, sea cucumber dredge net fishing was 0.204, and octopus drift fishing(*4) was 0.472. Note that stationary net and shrimp trawl net fishing(*5) are methods for catching multiple species of fish.

*2 One set of fishing equipment and group of boats for each fishing method is counted in units of "kato".

*3 Small bottom trawling net

*4 A fishing method involving attaching a net to a frame with teeth. A type of bottom trawling net

*5 A method of throwing a barrel with a device (isari) into the octopuses' territory to lure them out and capture them.

Conclusion

Collection and accumulation of data has progressed with the spread of Smart Fisheries, which has made it possible to assess fisheries from a variety of perspectives. Environmental impact indicators are one example of this, and while they only cover the production process, should similar indicators be calculated for the processes of processing, and distribution in future, they could be used by restaurants and retailers as indicators for consumers, much like Eco-Score.

Squid sashimi from Hakodate may be visually transparent, but after becoming aware of the environmental impacts of squid fishing, it has recently come to seem murkier in my mental image. However, I hope that these environmental impact indicators will not be used to support or reject a particular fishing method, but will rather be used in planning proposals for Japan's fisheries policy.

Finally, I would like to finish by restoring the reputation of squid fishing. Environmental impact indicators only assess fishing methods from the perspective of their environmental impact; if assessed from the perspective of resource management, fishing methods that can control catches are generally superior to net fishing methods. Even among these, squid fishing is the most automated fishing method in the world. This method is particularly excellent as it does not catch any fish other than squid, and catch volume can be controlled down to an individual squid. Hakodate is the birthplace of squid fishing robots, and it is very possible that AI-equipped squid fishing boats and squid fishing robots will greatly improve the environmental impact indicators of squid fishing in future. The IQ method is now being implemented for fishing species other than squid, and this will also contribute to improving environmental impact indicators.

The above was an introduction to Fisheries GX, which is in the process of being implemented with a view to achieving carbon neutrality by the year 2050. It will be interesting to see our dinner tables in a decade from now.

- The first page

- Previous page

- page 1

- Current page: page 2

- 2 / 2

WADA Masaaki (Professor, Future University Hakodate and Director, Marine IT Lab, Future University Hakodate)

Born in 1971. Earned a graduate degree from Hokkaido University’s Graduate School of Fisheries Sciences. Doctor of fisheries science. After working in the private sector at Towa Denki Seisakusho, Wada was appointed as a professor at Future University Hakodate, where he is engaged in supporting the wild-catch and aquaculture industries through the use of IT. His published works include Embarking on Marine IT (Marin IT no shuppan; FUN Press); he was also involved in editing Introduction to Smart Fisheries (Sumato suisan-gyo nyumon; Midori Shobo).

The issue this article appears

No.63 "Fishery"

Our country is surrounded by the sea. The surrounding area is one of the world's best fishing grounds for a variety of fish and shellfish, and has also cultivated rich food culture. In recent years, however, Japan's fisheries industry has been facing a crisis due to climate change and other factors that have led to a decline in the amount of fish caught in adjacent waters, as well as the diversification of people's dietary habits.

In this issue, we examine the present and future of the fisheries industry with the hope of passing on Japan's unique marine bounty to the next generation. The Obayashi Project envisioned a sustainable fishing ground with low environmental impact, named "Osaka Bay Fish Farm".

(Published in 2024)

-

Gravure: Drawn Fishery and Fish

- View Detail

-

A History of Japan’s Seafood Culture: Focusing on Fermented Fish

SATO Yo-ichiro (Director General, Museum of Natural and Environmental History, Shizuoka; and Emeritus Professor, Research Institute for Humanity and Nature)

- View Detail

-

The Future of Our Oceans, Marine Life, and Fisheries: Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation

MATSUDA Hiroyuki (Emeritus Professor and Specially Appointed Professor, Yokohama National University)

- View Detail

-

What Will Be on the Table in 10 Years?: The Challenge of Fisheries GX

WADA Masaaki (Professor, Future University Hakodate and Director, Marine IT Lab, Future University Hakodate)

- View Detail

-

Fishery This and That

- View Detail

-

OBAYASHI PROJECT

Osaka Bay Fish Farm - Shift from the Clean Sea to the Bountiful Sea

Concept: Obayashi Project Team

- View Detail

-

FUJIMORI Terunobu’s “Origins of Architecture” Series No. 14: Seagrass Houses

FUJIMORI Terunobu

(Architectural historian and architect; Director, Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum; and Emeritus Professor, University of Tokyo) - View Detail

-

Fish Culture This and That

- View Detail