FUJIMORI Terunobu’s “Origins of Architecture” Series No. 15:

Japanese Datum of Leveling Monument

FUJIMORI Terunobu

(Architectural historian and architect; Director, Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum; and Emeritus Professor, University of Tokyo)

Photo courtesy of the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (GSI).

Maps in the past were created solely based on the shape of the terrain, but today, topographic maps clearly show contour lines that indicate elevation in addition to shape. These contour lines make it possible to cross roads, control the flow of rivers, and develop residential areas on slopes in familiar areas without any doubt.

Moving down the contour lines on a topographic map always brings us to the coastline at sea level eventually, while moving up the contour lines brings us to the top of a mountain, with a triangulation point and its elevation marked on the map.

Anyone who has used a topographic map before would know the above, but how are the elevations of contour lines and triangulation points determined? More specifically, where are these elevations measured from in the course of their determination? Even if one were to go to the coast to determine a reference point for zero sea level, they would be unable to do so because the tides rise and fall and the waves come and go as with any beach that we might recall. The margin of error in this scenario easily exceeds one meter. The only way to reduce the margin of error to close to zero is to use a single reference point somewhere on Japan's territory, from which the entire country is then surveyed.

The first to tackle this problem was the Land Survey Department of the Army during the Meiji era, the predecessor of today's Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (GSI). In 1891, the Land Survey Department marked a point in the front yard of the Army Ministry, to which it belonged, as a reference point, and set the sea level at Aburatsubo, located 24.5 meters below this point, as zero sea level. The elevation of all locations in Japan has since been determined by drawing contour lines based on the height measured from this reference point.

The reference point used to determine elevation in Japan's territory is called the "datum of leveling," and it can still be found today in a corner of the garden of the Parliamentary Museum, which stands on the site of the former Army Ministry beside the National Diet Building.

Photo courtesy of the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (GSI).

When I first started the activities of the Tokyo Architecture Detectives nearly half a century ago, I learned of the existence of this reference point through the architecture literature of the Meiji era and made an eye-opening visit to the site. Contrary to my expectations of a Meiji-era monument in the form of a small brick hut, I found a small stone building in the style of an ancient Roman temple standing majestically in the shade of the trees.

As I approached the building, I could see the words "Empire of Japan" (大日本帝國) embossed on the horizontal stone beam from right to left, as well as "Datum of Leveling" (水準原點) on the front wall. It is almost impossible to encounter the five Japanese characters for "Empire of Japan" in Japan today.

Photo courtesy of the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (GSI).

After taking a breath, I took my time to examine the architecture of the building. The person who designed the building must have chosen the classical style of architecture, which was inspired by ancient European architecture, because it had already been established as a style appropriate for national monuments by the time this building was constructed in the early Meiji era. The classical style had two origins, Greek architecture and Roman architecture, so I looked more closely to find out which style the building was based on.

Both Greek and Roman architecture had a pediment (triangular gable) on the facade, but there is a difference in the way the columns were positioned: Greek architecture typically had columns on all four sides, while Roman architecture only had columns on the facade. If we look at column capitals, which are key to the style, Greek architecture had three distinct orders: the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders. Roman architecture added to these the composite order and the Tuscan order, which features a simple ring.

Given the building's columns on the facade only and its Tuscan-style capitals, it was no doubt built in the style of Roman architecture. But why Roman instead of Greek?

The difference between ancient Greek and ancient Roman architecture can be simply understood as "Greek quality versus Roman quantity." In order to conquer the world, Rome increased the scale of its cities, buildings, roads, and waterworks, and it developed construction technology with the goal of standardization in order to support its expansion. This process of scaling up was more prominent in civil engineering than in architecture, and surveying was becoming more advanced as a fundamental technology for civil engineering. The Roman Empire had flourished with the support of surveying technology. Perhaps the designer of the Datum of Leveling Monument was very much aware of this when he adopted the style of Roman architecture instead of Greek architecture, or maybe he had embossed the five characters for "Empire of Japan" with the Roman Empire in mind.

What made my visit to the site truly "eye-opening" was not just the building itself, but even more so my knowledge of its designer and his life during the Meiji era. He was SATACHI Shichijiro, among the first batch of graduates of the Imperial College of Engineering. Unlike three of his classmates (TATSUNO Kingo, KATAYAMA Tokuma, and SONE Tatsuzo), he gave up his career of spearheading the Meiji-era project of progress and expansion midway through his life, and according to his descendant, the poet KANEKO Mitsuharu, Satachi "spent his final days idly in quiet isolation as a cynic who stopped interacting with others." Kaneko remarked that "he probably resolved to do that upon realizing there was something in his temperament that prevented him from keeping up with the brutal, survival-of-the-fittest mindset and tempo of builders."

This monument is a magnificent work by Satachi when he was still a trailblazer leading the times enthusiastically alongside his classmates.

Of the four graduates in the last row, TATSUNO Kingo is on the far right, and SATACHI Shichijiro is second from the left. KATAYAMA Tokuma is fourth from the left in the second row (standing in front of Satachi), with one person separating him from SONE Tatsuzo.

- Current page: page 1

- 1 / 1

FUJIMORI Terunobu

(Architectural historian and architect; Director, Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum; and Emeritus Professor, University of Tokyo)

Born in 1946. Earned a graduate degree from the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Architecture. Fujimori’s major architectural works include Nira (leek) House, Takasugi-an, and the Mosaic Tile Museum, while his published works include Tokyo Project in the Meiji Era (Meiji no tokyo keikaku; Iwanami Shoten), Adventures of an Architectural Detective: Tokyo Edition (Kenchiku tantei no boken tokyo hen; Chikumashobo), and Fujimori Terunobu: How Architecture Works for People (Fujimori terunobu kenchiku ga hito ni hatarakikakeru koto; Heibonsha).

The issue this article appears

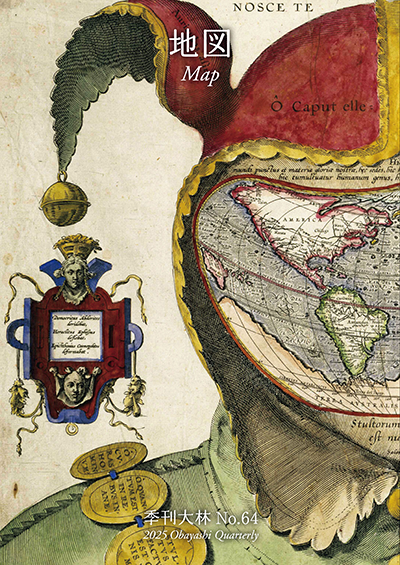

No.64 "Map"

Maps invite people into the unknown, and people get thrilled when presented with one―a simple sheet of paper.

From maps carved into rocks and historically ancient maps used in old times, to digital maps made by satellite in the modern era, we humans have been perceiving the world through a variety of maps.Not only do they help us visualize the world’s shape and overall appearance, but sometimes imaginary worlds are also constructed based on them.

In this issue showcasing various maps, we examine how people have been trying to view the world and what they are trying to see.In the Obayashi Project, we took on the challenge of deciphering and reconstructing in three dimensions a fictional city map called the Hashihara Castle Town Map (Hashiharashi Joka Ezu) drawn by Kokugaku scholar MOTOORI Norinaga when he was nineteen years old.

(Published in 2025)

-

Gravure: Is this also a map?

- View Detail

-

What Is a Map?

MORITA Takashi

(Professor Emeritus, Hosei University) - View Detail

-

The Frontiers of Maps: From the Present to the Future

WAKABAYASHI Yoshiki

(Professor Emeritus, Tokyo Metropolitan University) - View Detail

-

Visible World, Invisible World

OTA Akio

(Professor, Department of Visual Communication Design, College of Art and Design, Musashino Art University) - View Detail

-

The Dreams and Solitude of a Youth Who Drew Maps

YOSHIDA Yoshiyuki

(Honorary Director, Museum of Motoori Norinaga) - View Detail

-

OBAYASHI PROJECT

Deciphering the Hashihara Castle Town Map: The Imaginary Town of MOTOORI Norinaga

Speculative Reconstruction by Obayashi Project Team

- View Detail

-

FUJIMORI Terunobu’s “Origins of Architecture” Series No. 15: Japanese Datum of Leveling Monument

FUJIMORI Terunobu

(Architectural historian and architect; Director, Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum; and Emeritus Professor, University of Tokyo) - View Detail

-

Interesting Facts About Maps

- View Detail