The Dreams and Solitude of a Youth Who Drew Maps

YOSHIDA Yoshiyuki

(Honorary Director, Museum of Motoori Norinaga)

There is a map known as the Hashihara Castle Town Map (hashiharashi joka ezu). The Hashihara Castle Town is a fictitious town, and the map, of course, is also a product of the imagination. The map was accompanied by a genealogical table of the Lord Hashihara family and its vassals. Let us revisit this imaginary world once again.

Museum of Motoori Norinaga collection.

The town was conjured by a man called Ozu Yoshisada. He was in his 19th year and a native of Matsusaka in Ise Province. Or perhaps he had secretly adopted the Motoori family name. But in fact, he had used this family name because it was the proud family name of his ancestors who were vassals of the Kitabatake clan serving as provincial governor. This youth later become the Kokugaku, the study of classical Japanese literature, scholar Motoori Norinaga (1730-1801).

The Tale of Genji (genji monogatari) and the Kojiki are the first things that come to mind when Norinaga is mentioned.

He loved The Tale of Genji so much that he expounded on it for 40 years, and he even experienced occasional visions of Murasaki Shikibu paying him a visit as he was creating stylistic reproductions of the work. He also praised the fact that no other work in Japan or China, in the past and perhaps in the future, could match The Tale of Genji. These episodes would be in his later career, though.

Norinaga was also a devotee of the Kojiki. He believed that the work was edited and transmitted orally by Emperor Tenmu himself, and as such, it was a precious book without equal. He thus devoted himself to writing commentaries on the Kojiki, the 44-volume Kojikiden. Again, he did so later in his life.

There were a number of turning points in Norinaga's 72-year life.

One was at the age of 23, when he gave up his career as a merchant and relocated to Kyoto to become a doctor.

During his five and a half years in Kyoto, he studied Chinese classics and began to develop an interest in the fascinating and intriguing mystery of waka poetry and The Tale of Genji.

The second turning point was his meeting with Kamo no Mabuchi, also known as One Night at Matsusaka (matsusaka no hitoyo), and his decision to study the Kojiki at the age of 34.

These two turning points are widely acknowledged by all commentators on Norinaga.

Indeed, Norinaga prior to his relocation to Kyoto, or in other words, Yoshisada at the time of creating Hashihara Castle Town Map, differed quite significantly from his later image as a Kokugaku scholar.

He had probably barely heard of the Kojiki. I am not sure if he even knew the synopsis of The Tale of Genji. He might have been more interested in The Tale of the Heike (heike monogatari) than The Tale of Genji.

Yoshisada had always loved stories as a child. At the age of eight, he began learning Chinese characters by hand and eventually through The Thousand Character Classic (senjimon.) He also studied Confucianism through The Four Books of Great Learning (daigaku), Doctrine of the Mean (chuyo), Analects (rongo), and Mencius (moshi). In addition, he started to learn chanting at the age of 12 and appeared to have a talent for it, mastering 51 chants as a result.

Chants are composed of passages from classical literature and serve as anthologies of famous Japanese and Chinese anecdotes and poetry. They are a treasure trove of famous sites. These chants no doubt made an impression on not only the young Yoshisada's mind but also his cultural literacy.

Yoshisada enjoyed historical stories and wrote out the Enkodaishiden at the age of 14, and in the following year, he committed himself to memorize the entire story of the revenge of the forty-seven ronin that was recounted over many nights by an Edo preacher at the autumnal higan-e ceremony at Jukyo-ji Temple in Matsusaka before returning home. His prodigious ability for his age soon became the talk of the town. However, deserving of even greater attention than his excellent memory is his appetite for historical works, as can be seen from the Shinki Denjuzu and Shokugensho Shiryu, masterpieces produced in the same year that are as long as 10 meters long each, as well as Genealogies of the Emperor and Shogunate Families (honchoteio gosonkei narabini shogunke gokei).

Yoshisada was born in the town of Matsusaka, Ise Province, in 1730, during the latter half of Tokugawa Yoshimune's Kyoho Reforms, when the economy was still in recession. His family traded cotton in Edo. They were thus Edo merchants. The family's previously thriving business was in decline, and when Yoshisada was 11 years old, his father passed away and his family moved from their main residence to their secondary residence in Uomachi. However, as the Ozu family was a prominent family in the town, their children received a good education.

The Shinki Denjuzu mentioned above is a detailed genealogical table of Chinese emperors and their families during the four thousand years from the mythological Chinese emperors of ancient times to the Qing Dynasty. The Shokugensho Shiryu, on the other hand, is a study of the system in Japan. The young Yoshisada believed that the system in China based on revolution through dynastic change was completely different from that in Japan, which maintains a structure of continuous rule with the emperor at the top even as statesmen change. This marked the beginning of his gravitation toward having respect for continuity.

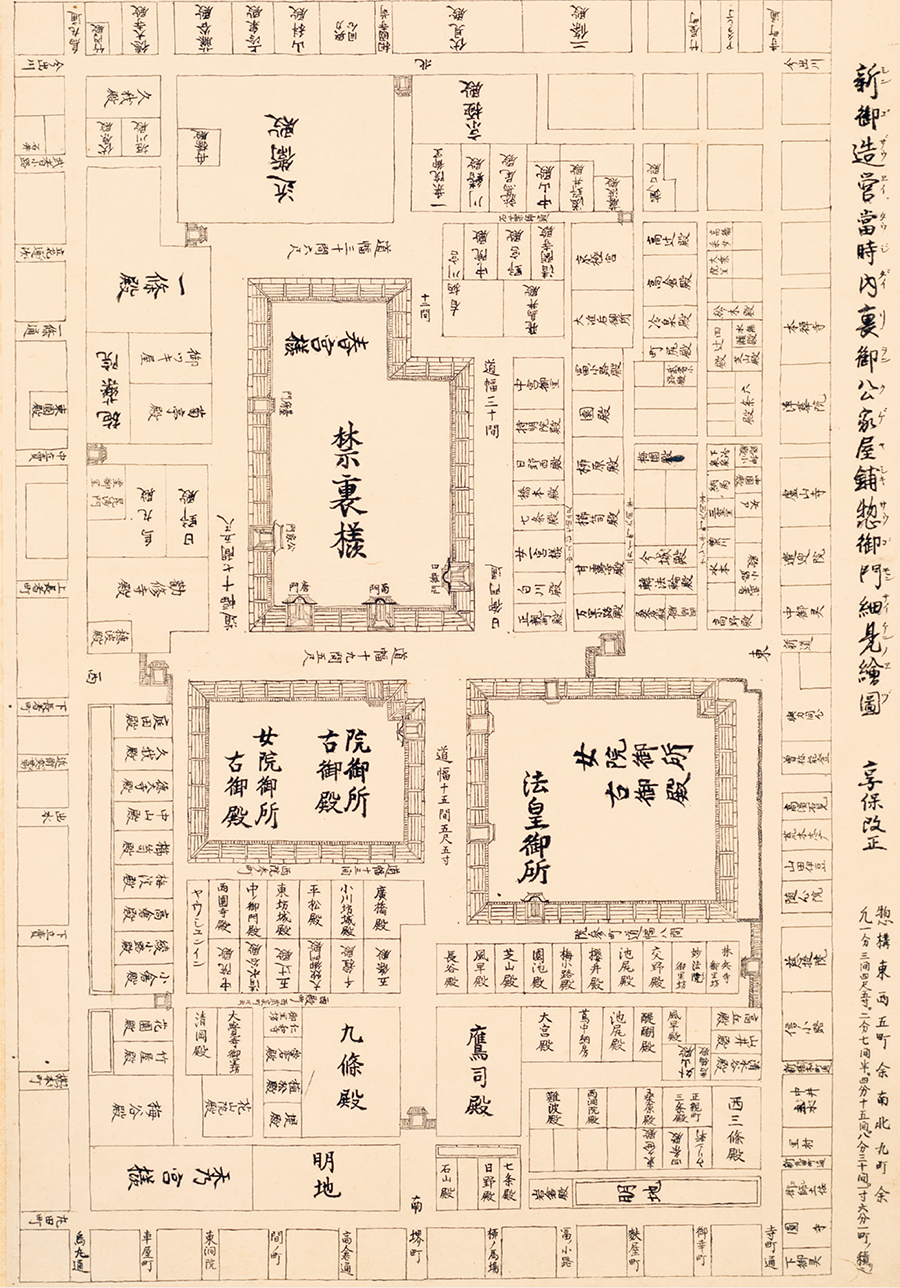

Another point of interest is the five imperial palace floor plans, including Imperial Palace Map (kyujo sashizu), at the end of the Shokugensho Shiryu. In addition to his interest in the Kyoto Imperial Palace, his drawing techniques and penmanship in these drawings were also reflected in [Kyoho Reforms] Detailed Map of the Buildings and Gates of the Imperial Palace at the Time of New Construction ([kyoho kaisei] shin gozoei toji dairi onkuge yashiki so gomon saiken no ezu) (photo), which is believed to have been created around the same time, as well as in Map of the Four Seas under the Heavens of Japan (dainihon tenka shikai gazu), a major work produced when he was 17, and further in Hashihara Castle Town Map.

Museum of Motoori Norinaga collection.

We are getting ahead of ourselves. Let us return to the period when Yoshisada was 15 years old. He came of age at the end of that year. Having become a young man, he completed his training and began his apprenticeship as a merchant in Odenmacho of Edo the following year.

Right before he left for Edo, Yoshisada produced a guidebook of his hometown Matsusaka titled Iseshu Iitakagun Matsusaka Shoran. Despite being a small booklet, it was the earliest extant geographical work of Matsusaka. It describes the history of Matsusaka as well as places of interest in the vicinity. This was perhaps Yoshisada's homage to Matsusaka before his departure. This also foreshadowed his praise of Ise Province (Tamagatsuma) in the final days of his life many years later.

In Iseshu Iitakagun Matsusaka Shoran, Yoshisada made a groundbreaking attempt to elucidate the configuration of the town both vertically and horizontally. This eventually gave form to his vision of an ideal town.

His interest in geography and the configuration of the area gradually set the stage for what was to come.

In the end, Yoshisada's stay in Edo ended after one year, although the circumstances remained unclear. Perhaps realizing the vastness of Japan along the way and during his stay in Nihonbashi, he drew a large map called Map of the Four Seas under the Heavens of Japan measuring 1.2 meters in length and 2 meters in width upon his return. This map contains the names of 3,019 places and 254 castle lords. It is also packed with information on fictitious places such as Kankara and Raretsu Province (Meshima) as well as the birthplace of Ono no Komachi. However, there is something frightening about maps. Although the 17-year-old Yoshisada would eventually gain recognition as Norinaga, his world would be bound by this single map that depicts Ezo-chi, parts of Ryukyu Province, and Oyashimaguni (the ancient name for Japan). Do people continue to live within the maps they have drawn?

Museum of Motoori Norinaga collection.

Following his return from Edo, Yoshisada drew a map of Japan at the age of 17 and began living at home. The son of the Ozu household could not face his late father and the world after having thrown in the towel and returned home after just one year. Yoshisada was told not to go outside as doing so would look bad, but since there were many things he wanted to do, he took this opportunity to remain in his room and began writing Toko Bassho in early autumn.

He also wrote out geographical works of Kyoto and works such as The Tale of the Heike set in Kyoto from cover to cover. He wrote a total of six volumes. This idea of a place (topos) being associated with a history and stories may have been related to chants, but above all, Yoshisada was strongly drawn to Kyoto. He continued to draw the Rakugai Sashizu, a map of the area around Kyoto.

He also began studying poetry on his own at the age of 17 or 18 as he wanted to recite poems. He recorded the annotations in Wakanoura, which he continued to write during his time in Kyoto, and it eventually grew into Norinaga's poetry treatise Ashiwake Obune.

Regardless of the beliefs of those around him, Yoshisada respected continuity and was interested in the configuration of land and towns. He firmly constructed his own world through waka poetry and his attraction to Kyoto, the culmination of which being his creation of works such as Hashihara Castle Town Map and genealogical tables.

Norinaga was on a trip to Kyoto at the time of working on this map.

On one of these days, April 13, Norinaga left his accommodation east of the Sanjo Ohashi Bridge and traveled from the Kodo and Shimogoryo Shrine to Otsuijinouchi, Kinri, the Kyoto Sento Imperial Palace, and the residences of various nobles. He then made his way from Shokoku-ji Temple to Kamigamo Shrine, Midorogaike Lake, Shimogamo Shrine, Hyakumanben, Yoshida, before finally arriving at Kurodani to visit the Hojo, where he also paid his respects before ancestral Buddha statues and visited the mausoleum, which is said to be for Shoseiin. He then rounded off the day's itinerary with a visit to Shinnyo-do Temple. His packed tour of Kyoto lasted more than a month, but of particular interest were his visits to Otsuijinouchi, Kinri, the Kyoto Sento Imperial Palace, and the residences of various nobles. The tour served as an on-site survey for Detailed Map of the Buildings and Gates of the Imperial Palace at the Time of New Construction, but in his mind, he might have also imagined himself walking through the Hashihara Castle Town.

So, what happened to this imaginary world depicted in Hashihara Castle Town Map and the Hashihara family's genealogical table?

Did the world of the Hashihara family vanish without a trace when Yoshisada became Norinaga?

I doubt so. After eventually changing his name to Norinaga, he immersed himself in the world of The Tale of Genji through his experiences in Kyoto, his readings, and his creation of detailed chronologies, and even as he lamented the dearth of historical materials that remained, he created the massive imaginary world of the Kojikiden. This could be seen as building on his previous work by altering its time and place from the reign of the Hashihara family, through the Heian period, to the mythological age.

- Current page: page 1

- 1 / 1

YOSHIDA Yoshiyuki

(Honorary Director, Museum of Motoori Norinaga)

Born in 1957. Graduated from the Faculty of Letters, Kokugakuin University. After working as a researcher at the Museum of Motoori Norinaga, he was appointed Director of the museum in 2009. He was then appointed Honorary Director in 2020. Chairperson of Suzunoya Ruins Preservation Association. His major publications include Imitating Norinaga: How to Live a Life of Aspirations (Norinaga ni manebu: kokorozashi wo kantetsusuru ikikata) and Motoori Norinaga: The Words in the Hearts of the Japanese People (Motoori norinaga: nihonjin no kokoro no kotoba).

The issue this article appears

No.64 "Map"

Maps invite people into the unknown, and people get thrilled when presented with one―a simple sheet of paper.

From maps carved into rocks and historically ancient maps used in old times, to digital maps made by satellite in the modern era, we humans have been perceiving the world through a variety of maps.Not only do they help us visualize the world’s shape and overall appearance, but sometimes imaginary worlds are also constructed based on them.

In this issue showcasing various maps, we examine how people have been trying to view the world and what they are trying to see.In the Obayashi Project, we took on the challenge of deciphering and reconstructing in three dimensions a fictional city map called the Hashihara Castle Town Map (Hashiharashi Joka Ezu) drawn by Kokugaku scholar MOTOORI Norinaga when he was nineteen years old.

(Published in 2025)

-

Gravure: Is this also a map?

- View Detail

-

What Is a Map?

MORITA Takashi

(Professor Emeritus, Hosei University) - View Detail

-

The Frontiers of Maps: From the Present to the Future

WAKABAYASHI Yoshiki

(Professor Emeritus, Tokyo Metropolitan University) - View Detail

-

Visible World, Invisible World

OTA Akio

(Professor, Department of Visual Communication Design, College of Art and Design, Musashino Art University) - View Detail

-

The Dreams and Solitude of a Youth Who Drew Maps

YOSHIDA Yoshiyuki

(Honorary Director, Museum of Motoori Norinaga) - View Detail

-

OBAYASHI PROJECT

Deciphering the Hashihara Castle Town Map: The Imaginary Town of MOTOORI Norinaga

Speculative Reconstruction by Obayashi Project Team

- View Detail

-

FUJIMORI Terunobu’s “Origins of Architecture” Series No. 15: Japanese Datum of Leveling Monument

FUJIMORI Terunobu

(Architectural historian and architect; Director, Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum; and Emeritus Professor, University of Tokyo) - View Detail

-

Interesting Facts About Maps

- View Detail