Deciphering the Hashihara Castle Town Map: The Imaginary Town of MOTOORI Norinaga

Speculative Reconstruction by Obayashi Project Team

5. A town with excellent environmental harmony and landscaping

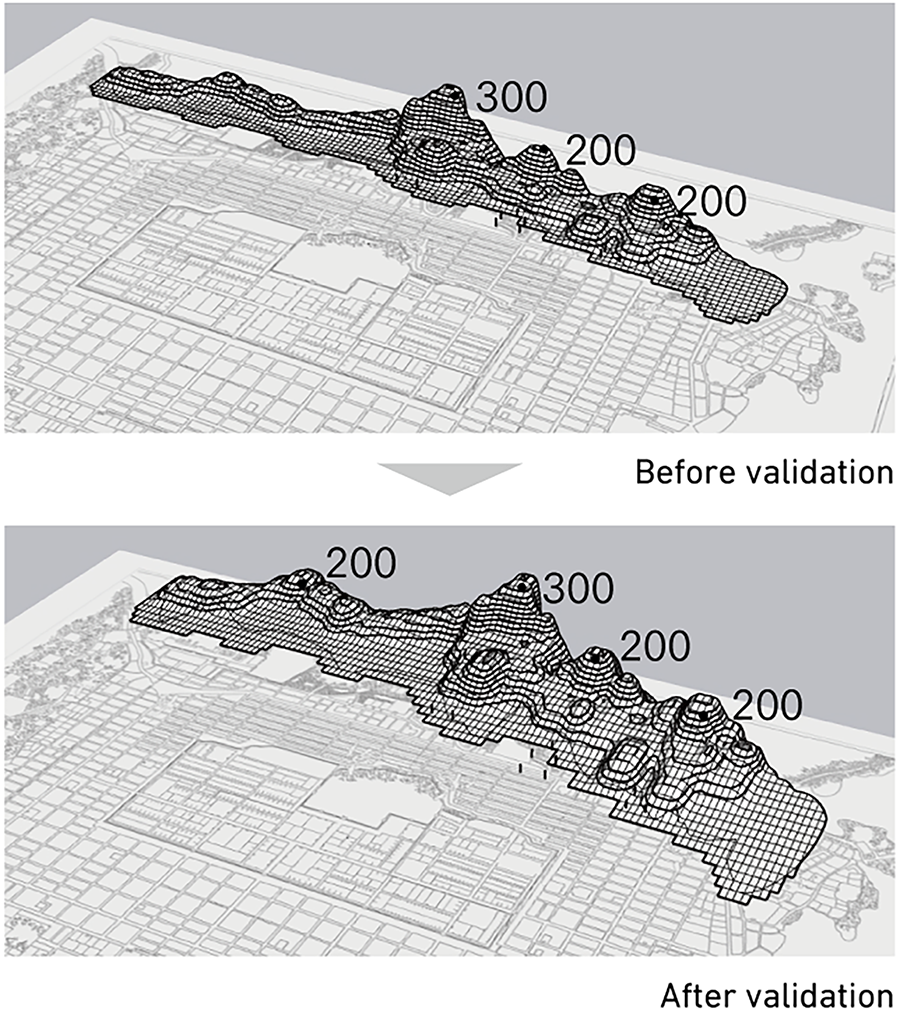

Validation of topographic features and elevation differences

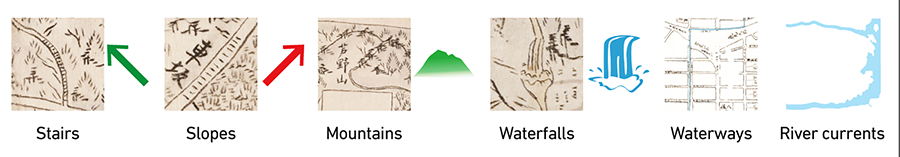

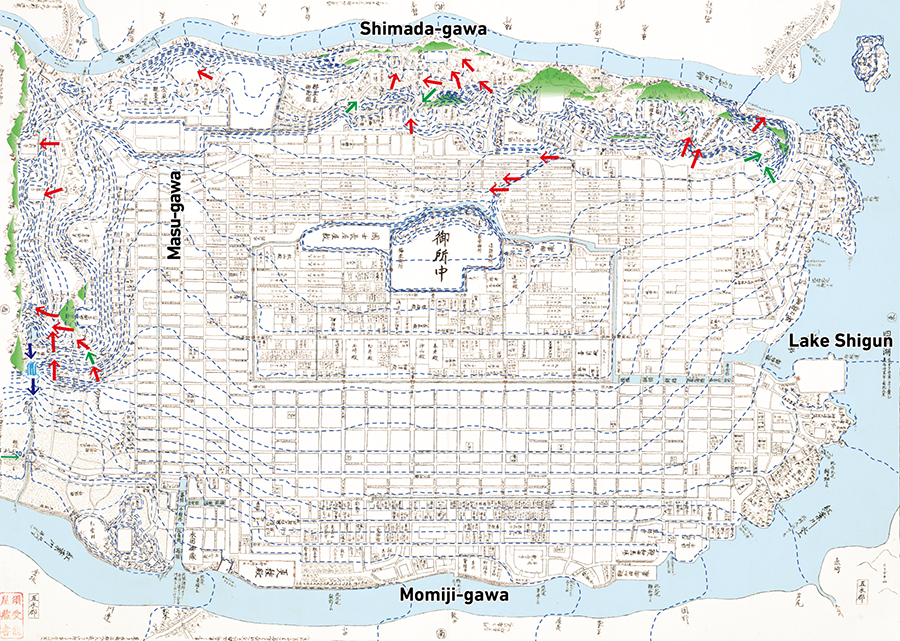

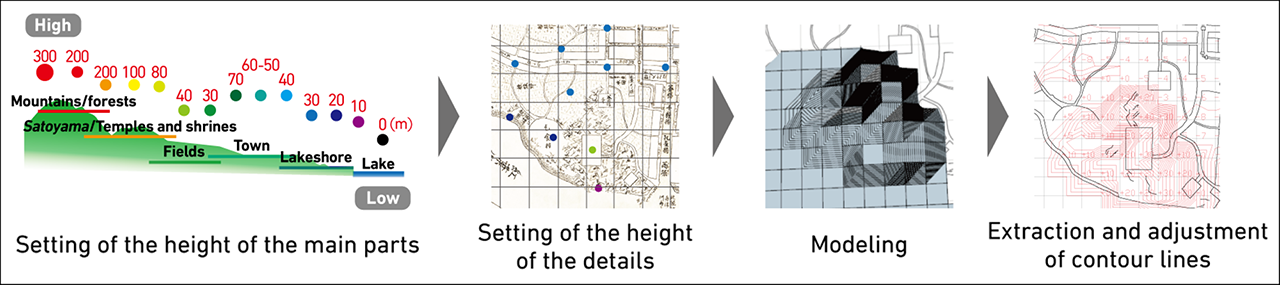

In order to create 3D renderings of the map, the project team set out to decipher the topography and validate the elevation differences on the map. The periphery of the map contains annotations for slopes and stairs used in old maps. In addition, multiple parallel lines indicating elevation differences were drawn between the north side of the imperial palace and the samurai residences, and detailed microtopographic features were also drawn in the town. The foothills of the mountains feature marks that appeared to represent waterfalls with a drop, indicating that the Hashihara castle town and its surrounding environment had a varied topography.

[Deciphering details]

[Reading topography from maps]

On the other hand, where rivers are concerned, it was common practice on old maps to write the names of rivers from upstream to downstream. Accordingly, Shimada-gawa on the north side flowed from west to east and into the lake. Momiji-gawa on the south side flowed from the lake in the east to the west. Furthermore, Masugawa-tori on the west side of the map showed Masu-gawa flowing from north to south. These observations suggest that the town center sloped from north to south and from east to west in a complex and discontinuous manner.

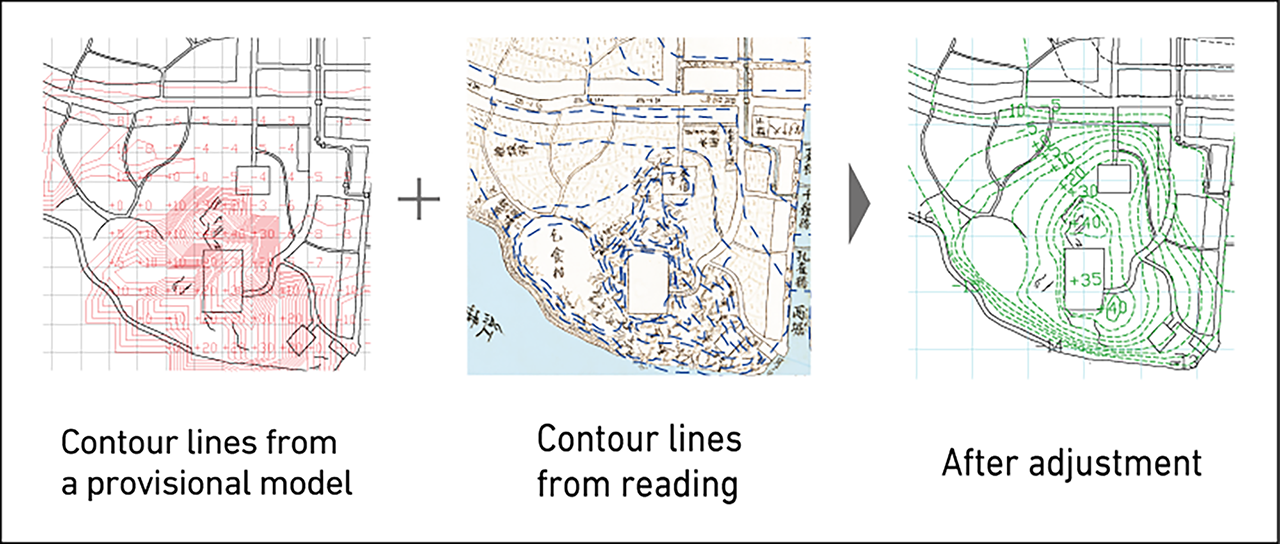

In addition, the project team conjectured that the entire Hashihara castle town had a slope of around 0.3% to 0.5% by comparing it with the riverbed gradient of Kamo-gawa in Kyoto and the topographic gradient of Matsusaka, which presumably would have influenced the young Norinaga. Using this information as a guide, the team then drew contour lines and carried out modeling by setting specific heights of key sites, before extracting contour lines from the model to elucidate the detailed topography of the town center.

[Creation of a provisional model]

[Extraction of contour lines from a provisional model]

[Adjustment by superposition]

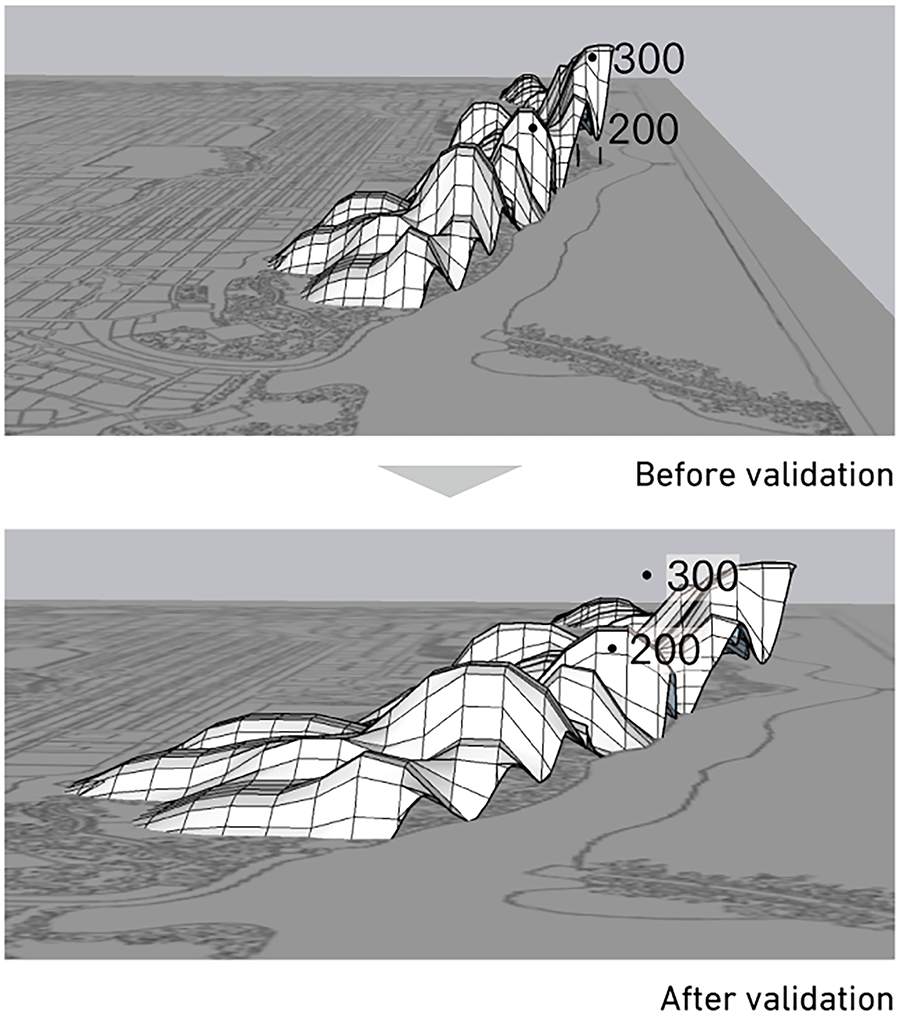

Estimating the height and distances of surrounding mountains

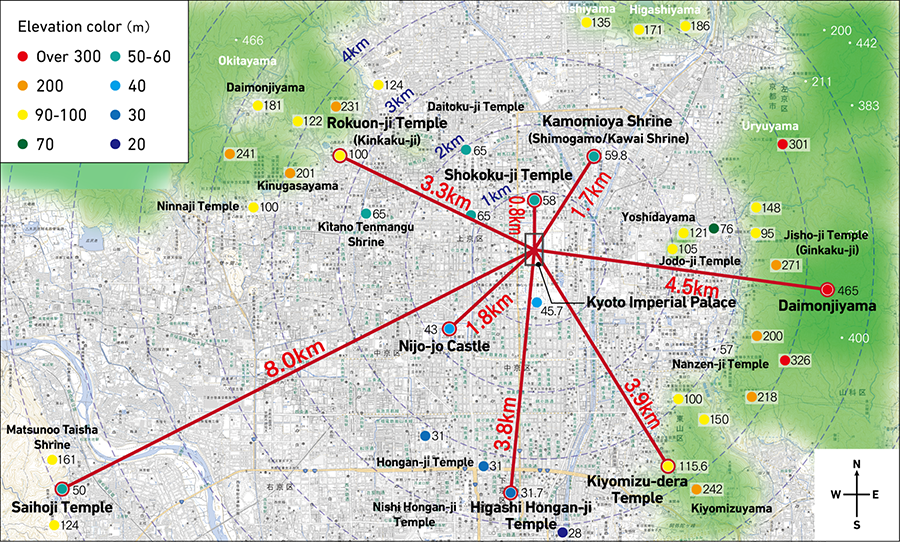

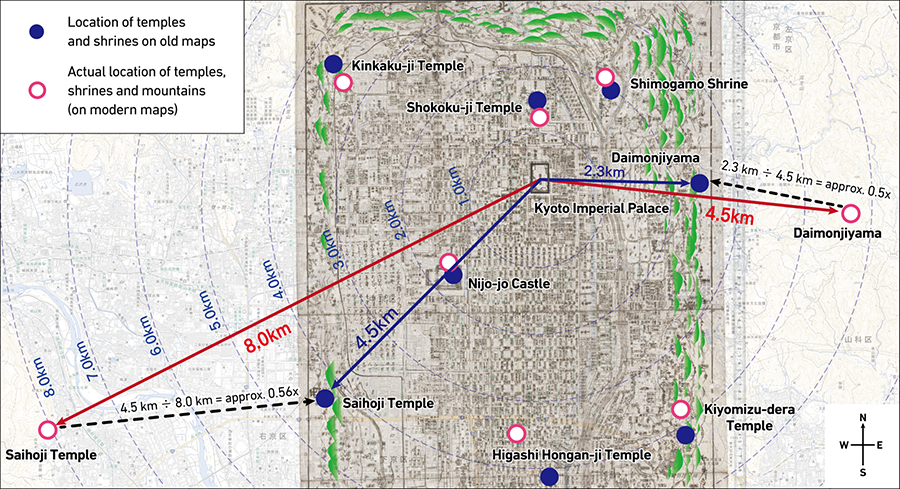

In typical old maps, mountains surrounding town or city centers were often drawn with compressed horizontal distances. Some clues regarding topographic representation could thus be obtained by comparing old maps of Kyoto made during that period with present-day maps.

[Actual distances from Kyoto Imperial Palace to major temples, shrines and mountains (○) and their heights]

[Comparison of the location of temples, shrines, and mountains on old and modern maps]

It was found that in old maps of Kyoto, even though the city center was drawn almost to scale, distances to the surrounding mountains and paths in the mountains were drawn with a ratio of one unit in the map's longitudinal direction for every half-unit in the latitudinal direction. If one were to attempt a three-dimensional rendering of the mountains based on the planar geometry of the old maps of Kyoto and the elevation of the mountains which would not have changed from the past to the present, the mountains would appear to be extremely steep. In creating 3D renderings of the Hashihara Castle Town Map, the height of the mountains was assumed to be around 200 to 300 meters by using the elevation of mountains in Kyoto as reference, and it was found that doubling the background distance of the mountains across the entire range in which they were drawn resulted in a natural shape for the mountains.

[Three-dimensional rendering of the mountains (1x height, 2x depth)]

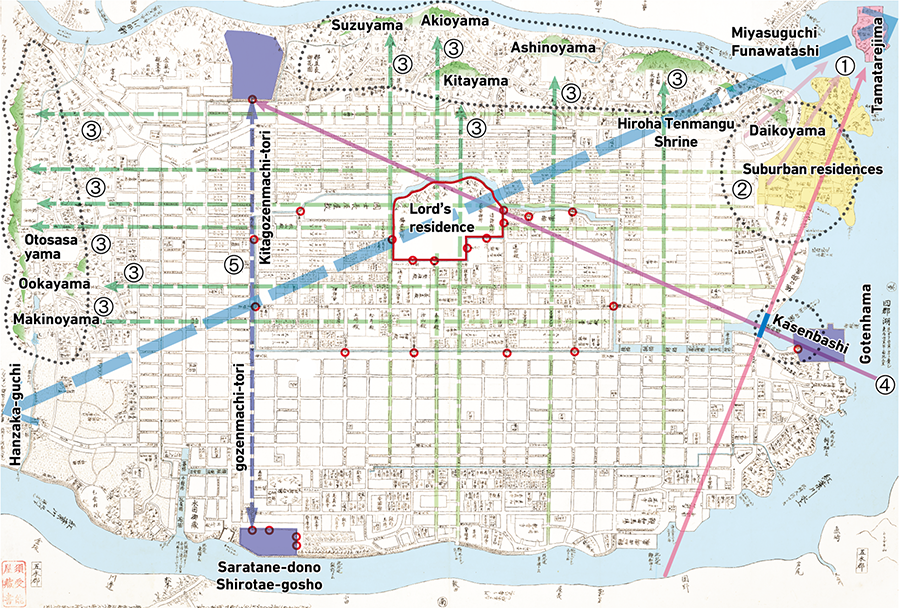

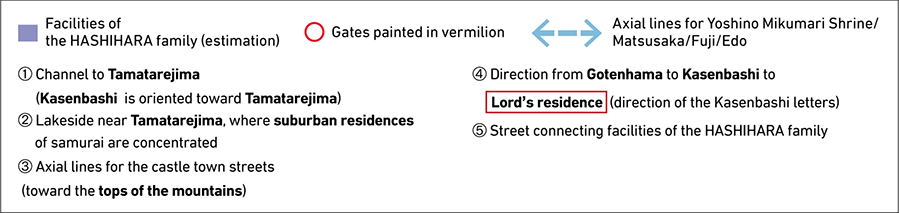

Reading townscape axes

Next, looking at the surrounding mountains and scenic spots depicted in the Hashihara Castle Town Map, as well as the relationship between them and the castle town, it seemed that Norinaga had also considered access to superior views and scenery. Some examples are as follows.

- ① The direction in which Kasenbashi crossed over the river formed an axial line toward the scenic spot Tamatarejima.

- ② Many suburban residences of samurai could be seen along the shore of the lake near Tamatarejima.

- ③ The peaks of the surrounding mountains lay on straight lines extended from highways and streets in the castle town.

- ④ The direction of the characters for Kasenbashi formed an axial line connecting Gotenhama to the imperial palace via Kasenbashi.

- ⑤ Gozenmachi-tori formed a townscape axis by connecting the mountains and waterfront with key facilities.

[Reading the townscape axes]

It is conceivable from ④ that Gotenhama served as a facility for holding banquets while enjoying views of the imperial palace over Kasenbashi. It is believed that the existence of these townscape axes is an indication of the importance Norinaga had placed on the visual relationship between the town and the surrounding mountains and scenic spots. With regard to ⑤, the facilities with vermilion gates (a site that appeared to be a facility of the HASHIHARA family on the mountain side [purple] and Koshu-den [Shirotae-gosho] on the waterfront side) were connected to each other. On the waterfront side, there were moats with bridges, storehouses, and docks, and in the middle of the axial line, there was a series of vermilion gates connecting the citadel area with the exterior.

Kasenbashi, the key starting point of a townscape axis, was thought to have been modeled after the shape of Sanjo Ohashi Bridge in Kyoto, which Norinaga had visited before creating the map. This is because the length of the bridge was 61 ken during Hideyoshi's rule and also in the range of 57 to 61 ken during the Edo period depending on the period of renovation, making it the same size as Kasenbashi.

Kasenbashi is presumed to be a large bridge with a drum bridge structure modeled after the Sanjo Ohashi Bridge in Kyoto.

A town that embodied both Norinaga's experiences and original scenery

What could be seen beyond the axial line extending toward the scenic spot Tamatarejima from the imperial palace?

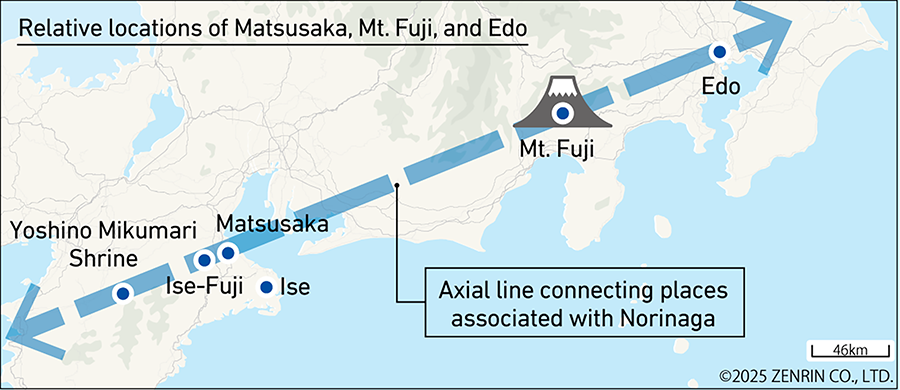

In the course of imagining the scenery envisioned by Norinaga, the project team superimposed this axial line onto the map of Japan. When placing the start of the axis at Norinaga's hometown of Matsusaka and extending it eastward, the axis formed a straight line that passed through Mt. Fuji and led to Edo. Conversely, extending the axis westward created an axial line that ran into Ise-Fuji and led to Yoshino Mikumari Shrine in Nara beyond that. In other words, if the axial line from the scenic spot Tamatarejima to the imperial palace was extended all the way to the west, it would create exactly the same angle as the direction from Matsusaka to Ise-Fuji or an axial line from Matsusaka toward Mt. Fuji and to Edo beyond that.

View of Mt. Fuji from Ise

Norinaga, who was born and raised in Matsusaka, may have placed a scenic spot in the two-o'clock, or northeastern, direction from the Hashihara castle town because of his memory and foundational experience of having enjoyed superior views in that particular direction.

In addition, Yoshino Mikumari Shrine was where Norinaga's father had prayed for a child, and Norinaga was told by his mother when growing up that he was born thanks to the shrine. Although this may be mere coincidence or a far-fetched interpretation, this town appeared to have embodied Norinaga's own experiences and imagined scenery in various forms.

Creating a rich natural environment and landscape

Finally, this paper would like to touch on the rich natural environment and diverse vegetation depicted by Norinaga.

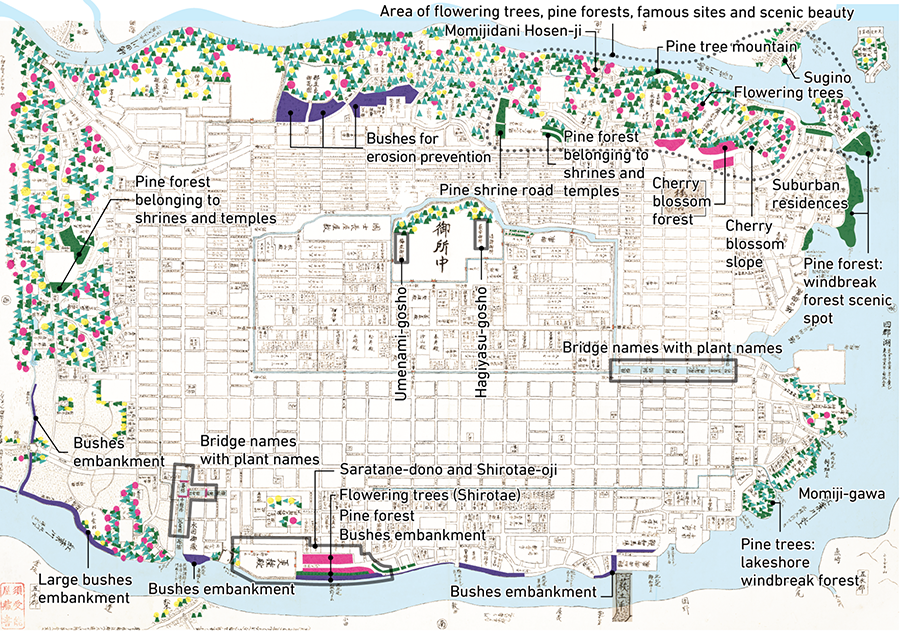

As outlined above, the surrounding mountains were depicted with a mixture of coniferous and broad-leaved trees. Also, pine forests along the lake and bamboo planted to prevent erosion of the riverbanks were meticulously drawn. In addition, in a small corner of the foot of the mountains overlooking Shimada-gawa, there was a temple called Momijidani Hosen-ji, which was surrounded by broad-leaved trees that were probably maple trees. Seasonal elements such as cherry trees and plum groves were also realistically depicted.

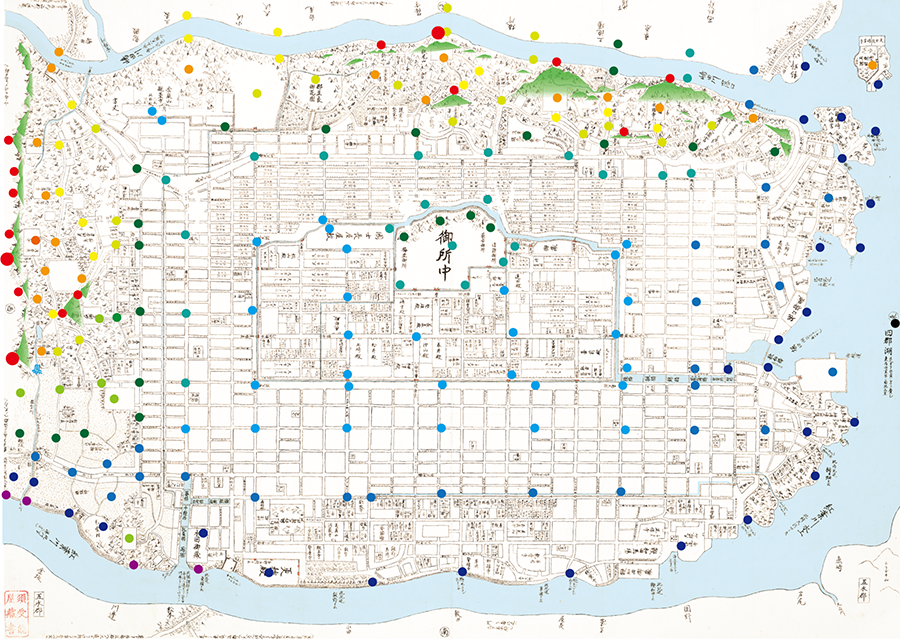

The project team first extracted pictures and words that corresponded to plants before proceeding to identify distinctive imagery such as pine trees. The team also deduced that the trees lining streets believed to be named after plants, such as Shirotae (*2) -oji, were trees of that name.

[Vegetation planting distribution map]

Furthermore, at the end of Shirotae-oji, there was a mansion called Koshu-den, which may be thought to have indicated a site with many white flowers and trees where people gathered. (*3)

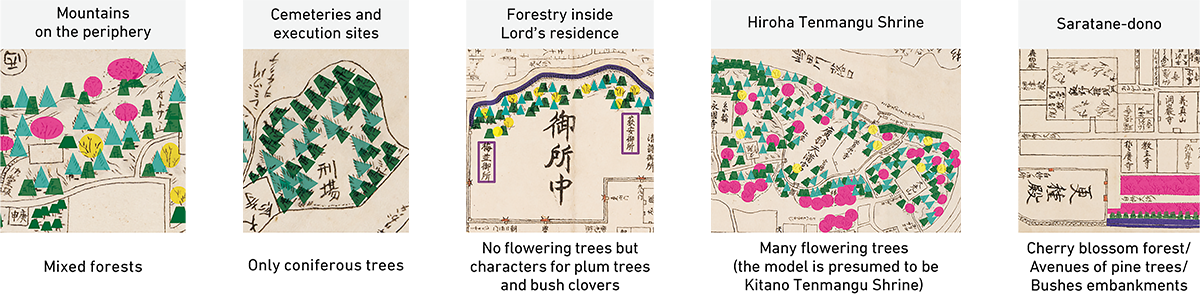

There were also some spots where pictures were annotated with words, such as "cherry blossom forest." To give further weight to these conjectures, the team conducted a comparative review using historical documents from the same period, such as Rakuchu Rakugai Zu and the Meisho Zue of the Edo period, to figure out the species of trees depicted on the map. The trees were also color-coded according to their species.

A forest of cherry trees extends within the precincts of Kiyomizu-dera Temple, and many broad-leaved trees thought to be maple trees are drawn around the temple.

The mountains in the background are covered with evergreen coniferous pine trees, but a few cedar trees can also be seen.

(Kobe University Library collection)

Source: Union Catalogue Database of Japanese Texts

https://doi.org/10.20730/100345432

From the professional viewpoint of landscaping and considering the environment of the time, the team deduced that the coniferous trees were probably cedar, cypress, and pine; the broad-leaved trees were katsura (caramel tree), maple, cherry, and plum; and that the forests were mixed forests with a good balance of these different trees. Norinaga may have imagined a beautiful satoyama landscape where colorful planted vegetation could be enjoyed in all seasons. He also drew paths for traversing mountain ridges and foothills, perhaps envisioning the sight of people enjoying the nature along ridge trails, valleys, waterfalls, temples, and the waterfront.

[Tree species arrangements that show Norinaga's intentions]

Several bridges in the castle town were named after plants as well, including katsura, maple, iris, white chrysanthemum, and kashiwa (emperor oak). In addition, annotations for the imperial palace included sites that contained the names of plants reminiscent of spring and autumn, such as Umenami-gosho and Hagiyasu-gosho.

The map depicts not only the castle town but also the surrounding mountains, lakes, and rivers to represent the diverse nature. The young Norinaga may have been attempting to capture both the urban and the natural as integral parts of the environment as a whole.

*2 Shirotae: White fabric woven from the fibers of paper mulberry bark ("Haru sugite / Natsu kitarurashi / Shirotae no / Koromo hoshitari / Ama no kaguyama," Empress Jito, Manyoshu). A variety of wild cherry tree. In his Sugagasa no Nikki, Norinaga likened the cherry blossoms blooming all over Tanzan Shrine in Tonomine, Nara, to shirotae: "Kokomo kashikomo shirotae ni sakimichitaru hana no kozue."

*3 A poem by Bai Juyi used the word "geng zhong" (transliterated as "koshu" in Japanese) in the following passage to describe how the interior of a mansion was filled with flowers: "Ling gong tao hua man tian xia / He yong tang qian geng zhong hua."

[Column] Where was Norinaga?

The Hashihara Castle Town Map is a fictitious map, but if Norinaga had drawn it as his ideal town, where was Norinaga in this town? Since there are no extant records of Norinaga writing about this map, the following is entirely based on imagination, but let us venture a thought.

Although Norinaga was a townsman, he had a strong interest in war chronicles such as The Tale of the Heike and genealogical tables since he was a child. Considering these facts and the intricate details of the Genealogical Table of the HASHIHARA Family, it is likely that Norinaga had projected himself not as a townsman but as someone in the genealogical table.

At the age of nineteen when he drew the map, Norinaga had already lost his father and had to serve as head of the family despite his young age. At the same time, he was single and had no children. If we look for someone in a similar situation as he was, a person named SAKAIDA Musashinokami, a senior vassal with the rank of "On'ozamurai," catches our attention.

Although SAKAIDA Musashinokami was married, he was nineteen years old, the same age as Norinaga then, and had no children. He had two younger brothers, whose childhood names were Kyojiro and Kyozaburo, suggesting that his childhood name was Kyotaro or Kyoichiro.

Norinaga's attraction to Kyoto, his ideal town in real life, can be felt everywhere on the map. If Norinaga had projected himself as SAKAIDA Musashinokami, it would seem to be a means by which he secretly incorporated his attraction to Kyoto into not only the map but also the genealogical table.

Let us take a look at the location of SAKAIDA Musashinokami's residence on the map (refer to [Deciphering the Hashihara Castle Town Map]). His main residence was located facing away from Nakasuji, the main street, which echoes the location of Norinaga's house in Matsusaka against the Ise-kaido Road. SAKAIDA Musashinokami's suburban residence was located near Wano-no-watashi and boasted good views of the water transportation distinctive of this town. It was also close to the otabisho of Iino Gongen and would have been a place where the shrine's festivities could be enjoyed up close. Indeed, this was the perfect location for experiencing the town's vibrant culture.

Conclusion

As outlined above, the project team created 3D renderings of the fictitious the Hashihara Castle Town Map that nineteen-year-old Norinaga drew as he was weaving together a story, and deciphered the map down to its details. Through this validation process, the team believes that it has become clear that the map is not merely a fictitious map, but one that depicts an ideal town imagined by Norinaga which incorporated his vision of the town and its environment along with other multifaceted considerations.

Finally, over the course of this project, we received countless suggestions on how to decipher and interpret the Hashihara Castle Town Map and the Genealogical Table of the HASHIHARA Family from the Museum of Motoori Norinaga; YOSHIDA Yoshiyuki, Director Emeritus of the Museum of Motoori Norinaga; and Professor UESUGI Kazuhiro of Kyoto Prefectural University, who specializes in historical geography and cultural landscape studies.

The entire project team would like to express our gratitude to them once again.

- The first page

- Previous page

- page 1

- page 2

- page 3

- Current page: page 4

- page 5

- 4 / 5

- Next page

- The last page

The issue this article appears

No.64 "Map"

Maps invite people into the unknown, and people get thrilled when presented with one―a simple sheet of paper.

From maps carved into rocks and historically ancient maps used in old times, to digital maps made by satellite in the modern era, we humans have been perceiving the world through a variety of maps.Not only do they help us visualize the world’s shape and overall appearance, but sometimes imaginary worlds are also constructed based on them.

In this issue showcasing various maps, we examine how people have been trying to view the world and what they are trying to see.In the Obayashi Project, we took on the challenge of deciphering and reconstructing in three dimensions a fictional city map called the Hashihara Castle Town Map (Hashiharashi Joka Ezu) drawn by Kokugaku scholar MOTOORI Norinaga when he was nineteen years old.

(Published in 2025)

-

Gravure: Is this also a map?

- View Detail

-

What Is a Map?

MORITA Takashi

(Professor Emeritus, Hosei University) - View Detail

-

The Frontiers of Maps: From the Present to the Future

WAKABAYASHI Yoshiki

(Professor Emeritus, Tokyo Metropolitan University) - View Detail

-

Visible World, Invisible World

OTA Akio

(Professor, Department of Visual Communication Design, College of Art and Design, Musashino Art University) - View Detail

-

The Dreams and Solitude of a Youth Who Drew Maps

YOSHIDA Yoshiyuki

(Honorary Director, Museum of Motoori Norinaga) - View Detail

-

OBAYASHI PROJECT

Deciphering the Hashihara Castle Town Map: The Imaginary Town of MOTOORI Norinaga

Speculative Reconstruction by Obayashi Project Team

- View Detail

-

FUJIMORI Terunobu’s “Origins of Architecture” Series No. 15: Japanese Datum of Leveling Monument

FUJIMORI Terunobu

(Architectural historian and architect; Director, Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum; and Emeritus Professor, University of Tokyo) - View Detail

-

Interesting Facts About Maps

- View Detail